As New Yorkers begin to leave coastal areas in the coming decades, spurred by rising sea levels and storm flooding, the consequences could ripple across the city and lead to displacement in low-income neighborhoods in Manhattan, the Bronx and Brooklyn, a new report suggests.

The analysis is one of the first predictions of how climate change could reshape the city’s map this century, as higher-income families in waterfront areas move toward inland communities with relatively low rents and high housing stock.

The findings, the report’s authors say, underscore the need for a long-term plan to handle an inevitable population shift across the five boroughs, with nearly one-fifth of the city’s current population living in areas that will be at risk of regular coastal flooding by the 2050s.

“The entire city is going to feel climate migration in one way or another,” said Amy Chester, the managing director of Rebuild By Design, a climate adaptation consulting firm based in New York, and an author of the report. “We need to start this conversation about where our neighbors are gonna go.”

Over the past decade, the city has already begun to see some people moving out of areas most vulnerable to climate change, even as coastal areas see growing development.

In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, hundreds of families in Staten Island’s Oakwood Beach took state-funded buyouts, leaving a seaside community that saw perennial flooding. More recently, Hurricane Ida led some homeowners to call for buyouts in areas now considered vulnerable to flooding caused by intense rainfall.

The new report, from Rebuild By Design and Milliman, an insurance company, comes as the state plans to secure $250 million to fund the creation of a permanent buyout program, after voters last month approved a $4 billion bond act for environmental projects.

“What we're trying to say is that the city has a choice. We can either fortify our neighborhoods or we can retreat,” Chester said. “And either one should be made as a collaborative decision with the communities who live there. But the decision needs to be made pretty soon before we have rippling effects that we don't want.”

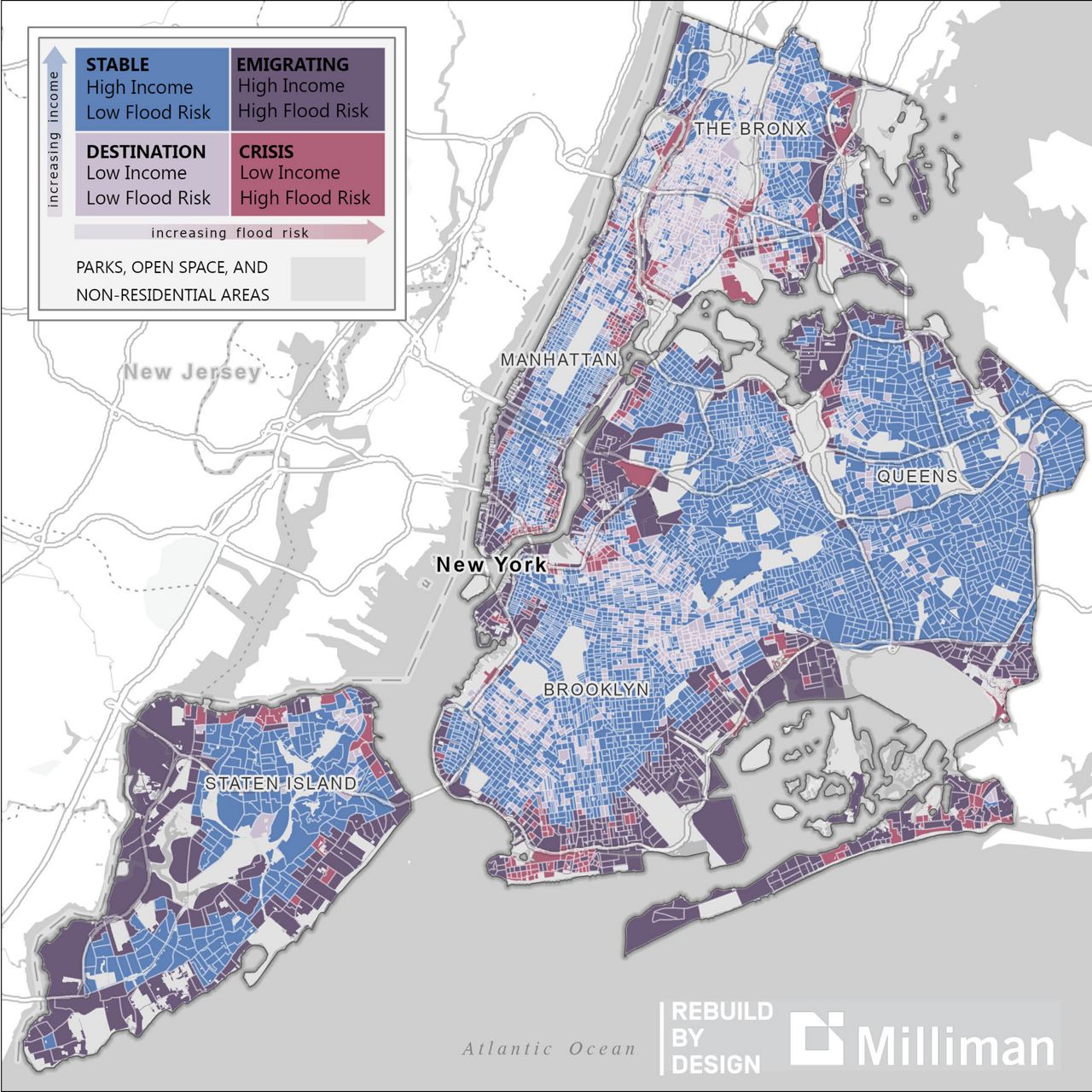

The report uses census data and maps of projected coastal flooding to separate the city into four areas: High- and low-income areas in the projected floodplain for the 2050s, and high- and low-income areas facing low flooding risks by the mid-century.

The former areas are likely to emigrate from their neighborhoods, though the low-income communities — labeled “Crisis” areas in the report — will likely need government resources to do so. The inland areas with largely low-income residents are likely to see a large influx of those emigrants, possibly leading to displacement of existing residents.

Neighborhoods on the city’s Atlantic coast, such as Coney Island, Arverne and Far Rockaway, as well as East Harlem and parts of Staten Island’s north coast, make up much of the “Crisis” area of the city, and cover about 500,000 city residents.

Inland neighborhoods projected to be “Destination” areas for climate migrants, with a total of 1.7 million residents, include Sunset Park, Borough Park, East New York and Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn; central Harlem and Washington Heights in Manhattan; and nearly the entirety of the South Bronx.

Both of these areas are majority non-white, with about two-fifths of families living below the federal poverty line.

Other, wealthier neighborhoods along the coasts – such as Breezy Point, Manhattan Beach, Greenpoint and Long Island City – may have to retreat as well, the report suggests. Yet those residents are likely going to be able to find housing in wealthier neighborhoods, causing relatively less displacement than in “Destination” areas.

Deborah Balk, a professor of public affairs at Baruch College who studies climate migration, said it is difficult to predict migration patterns at the scale of a single city. But, she added, in general, climate migrants do not move far if they can help it.

“It's a really reasonable assumption people are going to move near and where they have networks,” said Balk, who did not review the report.

Chester said she hopes the report can spark conversations in city government about creating a citywide plan to address population shifts caused by climate change. The plan, she said, will have to include ways to dramatically expand housing availability in the “Destination” zones, to both meet the housing needs of climate emigrants and keep those areas affordable for existing residents.

“I absolutely think that we have this space for more people,” Chester said. “The question is just, where and how to do it in ways that aren't going to create further displacement.”