Twenty years have passed since terrorists attacked the United States on Sept. 11, 2001, and its impact can still be felt through nearly every facet of American life.

Joe Biden has felt the ripples of the Sept. 11 attacks throughout his political career in a way few others have. Biden has perspective on 9/11 as a senator and as vice president — and as the nation mourns twenty years after the deadly attacks, as commander-in-chief.

Biden was serving in Congress when 9/11 occurred, and was himself instrumental in the early days — and years — of the wars in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

Biden’s stance on the wars has shifted somewhat in the decades since he first voted in favor of sending U.S. troops to Afghanistan in 2001, for which the 78-year-old has received both vilification and praise.

But common threads emerged in Biden’s response to the crisis. Long known for his ability to work across the aisle, it was Biden’s experience in foreign policy and bipartisanship that secured his role as Barack Obama’s vice president. Lawmakers and laymen alike have noted Biden’s compassion, often extended to military families and veterans, to which Biden has a personal connection — his son, Beau Biden, served a tour in Iraq and was a member of Delaware’s National Guard.

Here’s a look back at the president’s evolving view on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and how 9/11 shaped Biden’s presidency just under two decades before he ascended to the nation’s highest office.

Joe Biden was serving his fifth term as U.S. Senator to Delaware in 2001, and was also head of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee when the terrorist attacks occurred on Sept. 11.The following day, Biden went to the Senate floor to deliver a passionate speech condemning the attack, where he also previewed his view of American foreign relations in the years ahead.

“The future of organized terrorist cells is about to welcome the 21st century in a way that they never anticipated,” Biden said. “For in this dastardly act, they may have done what no other group of people could possibly have done — and that is to unite the civilized world. Unite our allies in Europe who share our values, unite our Russian friends, our Chinese friends. Unite the world.”

“Let there be no doubt: The United States, the civilized nations of the world, will unite and win this struggle,” Biden later added. “Our enemies will not, cannot defeat us.”

Biden’s speech foreshadowed the nearly-unanimous vote in the Senate days later, when 98 senators — Biden included — voted in favor of authorizing a resolution to approve “all necessary and appropriate force” in retaliation to those behind the 9/11 attacks.

On Oct. 7, 2001, then-President George W. Bush announced the United States would commence a series of airstrikes against the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan under “Operation Enduring Freedom,” the official government name for the U.S. and allied missions over the next 13 years.

Biden, along with many of his contemporaries, were vocally supportive of President Bush’s decision. In 2002, Biden also voted in favor of invading Iraq, and as chair of the foreign relations committee, assembled a group of largely pro-war testimony in favor of the move.

Ever the centrist, however, Biden over the next few years would walk the careful line between giving the executive branch authority to authorize military efforts, and concerns from Democrats that the Bush administration was not being transparent about where funds were going.

Between 2002 and 2005, Biden’s optimism about the U.S. presence in the Middle East began to wane. His initial support of the war rested on his belief that the United States had an obligation to foster nation-building in Afghanistan after ousting the Taliban.

“He had been very much of the view that you shouldn’t go in and just kill people and leave,” Jonah Blank, a former Biden aide, told Foreign Policy. “He felt in both moral and geopolitical terms that if you are invading a country, intervening militarily, then you do have a responsibility to leave it better than you found it.”

By 2005, when it became apparent that nation-building was making little progress, Biden became disillusioned with the wars, though still voted in favor of appropriating funds to troops involved in the overseas conflict. In 2007, Biden vocally opposed a troop resurgence in Iraq.

It is nearly impossible to discuss Joe Biden’s political career without mention of his oldest son, Beau Biden. Beau, who served as a member of the National Delaware Guard beginning in 2003, but was not enlisted for active duty until 2008.By that time, Joe Biden’s view of the wars both in Afghanistan and Iraq had shifted considerably.

Nonetheless, Biden continued to toe the political line. Before Beau’s deployment, when the senior Biden was in the midst of his second bid for president, Joe Biden famously said during Iowa’s 2007 State Fair: “I don’t want [Beau] going, but I tell you what — I don’t want my grandson or my granddaughters going back in 15 years and so how we leave makes a big difference.”

Still, Biden continued to vote in favor of measures to fund troops on the ground in both Afghanistan and Iraq, saying there was "no political point worth anybody’s life out there.”

Biden’s years of work on the Senate Foreign Relations committee would become a focal point of his presidential campaign, and ultimately served to help then-Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama nominate Biden as his vice-presidential candidate after Biden dropped out of the race in early 2008.

Obama reportedly even broached the job of secretary of state with Biden before the latter had officially accepted the offer to join the ticket as vice president, citing Biden’s “great interest in national-security policy, foreign policy.”

Ultimately, Biden decided he could have more sway in U.S. international relations as vice president.

During both his 2007 presidential and 2008 vice presidential campaigns, Biden focused heavily on withdrawing troops from Iraq, emphasizing (repeatedly, and somewhat ironically, given the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan) that there was “much more at stake in our security in the region depending on how we leave Iraq.”

The United States would start its lengthy withdrawal from Iraq in 2009, and President Obama announced the U.S. mission in Iraq formally ended in 2010. Troops would eventually be sent back in 2014 after the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) captured Mosul and began to systemically murder Yazidis in the country.

Around the same time as troops were starting to leave Iraq in 2009, Obama approved a resurgence of 21,000 troops to Afghanistan — a move about which Biden privately expressed skepticism.

Biden’s questioning was one of the early indicators that the vice president’s input would become crucial to the Obama Administration’s approach to relations with nations in the Middle East. Obama himself said at the time that Biden “really forces people to think and defend their positions, telling Politico in 2009: “I also know, when he gives me his advice, he gives it to me straight.”

Biden would go on to lead much of the United States’ military interference in both Iraq and Afghanistan, and made at least eight trips to visit Iraq during his first term as vice president.

While the first term of the Obama-Biden administration saw a surge of troops sent to Afghanistan, Obama pledged to remove all U.S. troops from the country before the end of his second term.

In October 2012, less than a month before Obama and Biden were reelected to that second term in office, Biden repeated the pledge that all troops would be out of the country by the end of 2014.

Those plans ultimately did not come to fruition. In late December 2014, American and NATO troops did formally end the combat mission in Afghanistan, although some remained as part of a support and training mission. President Barack Obama would later authorize U.S. forces to carry out operations against Taliban and al-Qaeda targets in the region.

But a subsequent plea from Afghan president Ashraf Ghani formally halted plans to withdraw all troops.

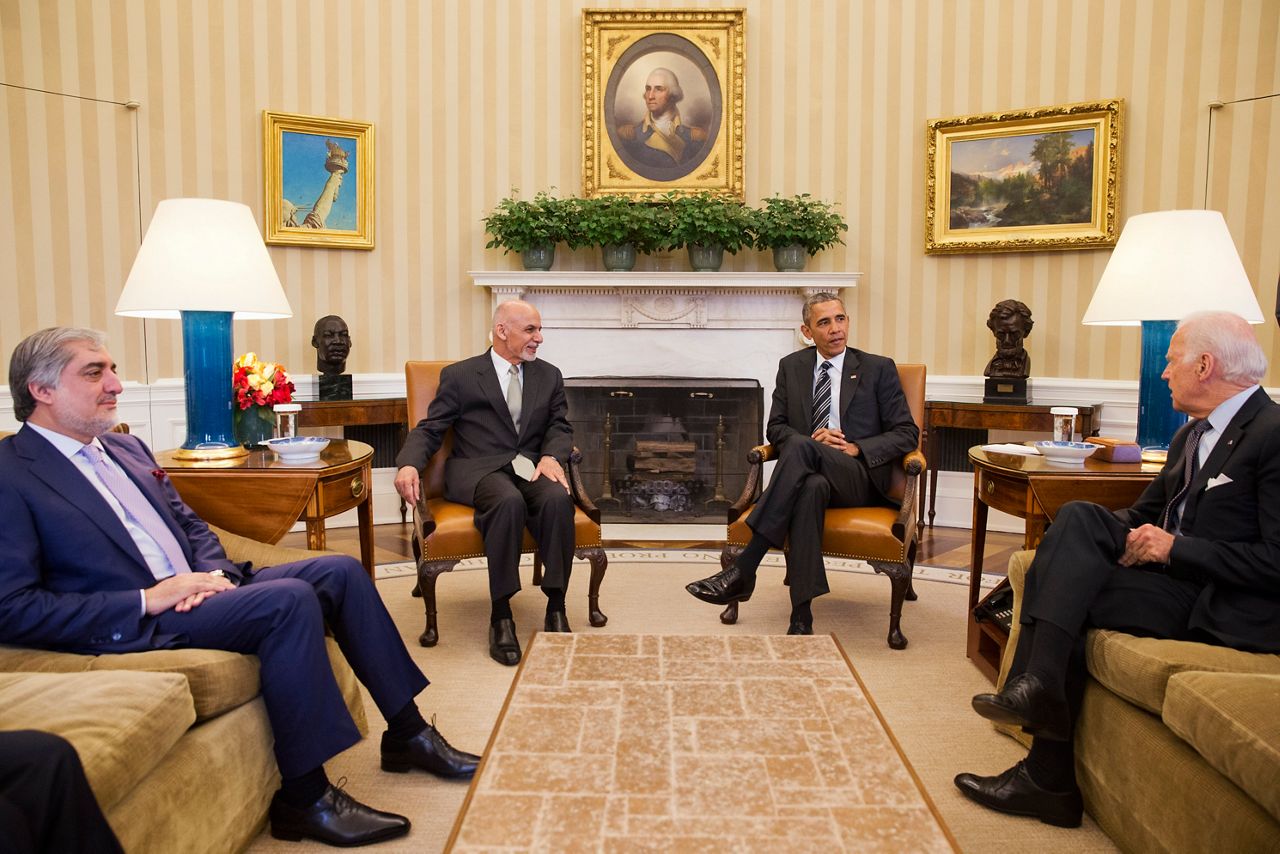

Biden was a key player in discussing American troop presence with Ghani, who in March 2015 visited Washington and met with both Biden and Obama.

Ghani began that trip by thanking the U.S. for its support over the previous decade-plus while also asking the Obama-Biden administration to slow its planned withdrawal of troops over the next year and beyond.

Obama heeded that call, leaving around 9,800 U.S. troops in the country through the end of 2015 instead of cutting the number in half, as originally planned. At the time, Obama maintained his goal of withdrawing all U.S. forces by the end of 2016.

By the time Barack Obama and Joe Biden left office in 2017, an estimated 8,400 troops remained in Afghanistan, a stark contrast to the promises made during their reelection campaign and second term in office.For the next several years, Biden remained relatively out of the public limelight, but did frequently criticize then-President Donald Trump for policies including, but certainly not limited to, Afghanistan and the Middle East as a whole.

When Biden officially declared his bid for presidency in 2019 he began to further reflect on some of his own decisions regarding the wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan, saying in the 2019 Democratic debate that he made a “bad judgment” in voting in favor of George W. Bush’s “shock and awe” campaign in Iraq. Biden also emphasized that he “opposed the surge in Afghanistan” during his time as vice president, adding the U.S., “should have not, in fact, gone into Afghanistan” in the way that it did.

Biden also incorrectly stated that he was against the Iraq war from “the moment” it started, a claim seized on by both his Republican opponent and Democratic rivals during the presidential primaries, and one he would go on to correct.

Biden outwardly campaigned on the promise to “end the forever wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East,” also pledging to “bring the vast majority of our troops home from Afghanistan and narrowly focus our mission on Al-Qaeda and ISIS.”

Biden also, in numerous campaign appearances and in his subsequent presidency, frequently invoked Beau Biden and his military service to connect with those currently enlisted in the army and their family members, as well as veterans.

It is this personal connection, in part, that has earned Biden the popular moniker of “Consoler-in-Chief.” Biden is known for his long conversations with military families, and for always carrying a card with him showing the number of U.S. troops who have died in the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East. Biden, to this day, ends the vast majority of his speeches with: “And may God protect our troops.”

By the time Biden was elected president, troop withdrawal from Afghanistan was already underway. That was thanks to the Trump administration, which in February 2020 struck a deal with the Taliban agreeing the group would no longer attack U.S. forces as long as the latter fully withdrew from Afghanistan by May 2021.

Biden in April 2021 changed that deadline to September, with all U.S. forces officially out of the country as of Aug. 31.

The departure will likely be remembered as chaotic and deadly. Harrowing videos of desperate Afghans clinging to departing planes, some then falling to their deaths, captivated the world in mid-August. Most were fleeing the Taliban, who quickly regained control of the country two decades after the group was pushed from power thanks to U.S. forces.

On Aug. 26, 13 U.S. servicemembers were killed when an ISIS-linked suicide bomber detonated explosives near the Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul. It was the deadliest attack on U.S. troops since Feb. 2020.

Five of those killed were only 20 years old, meaning they were born soon before the Sept. 11 attacks.

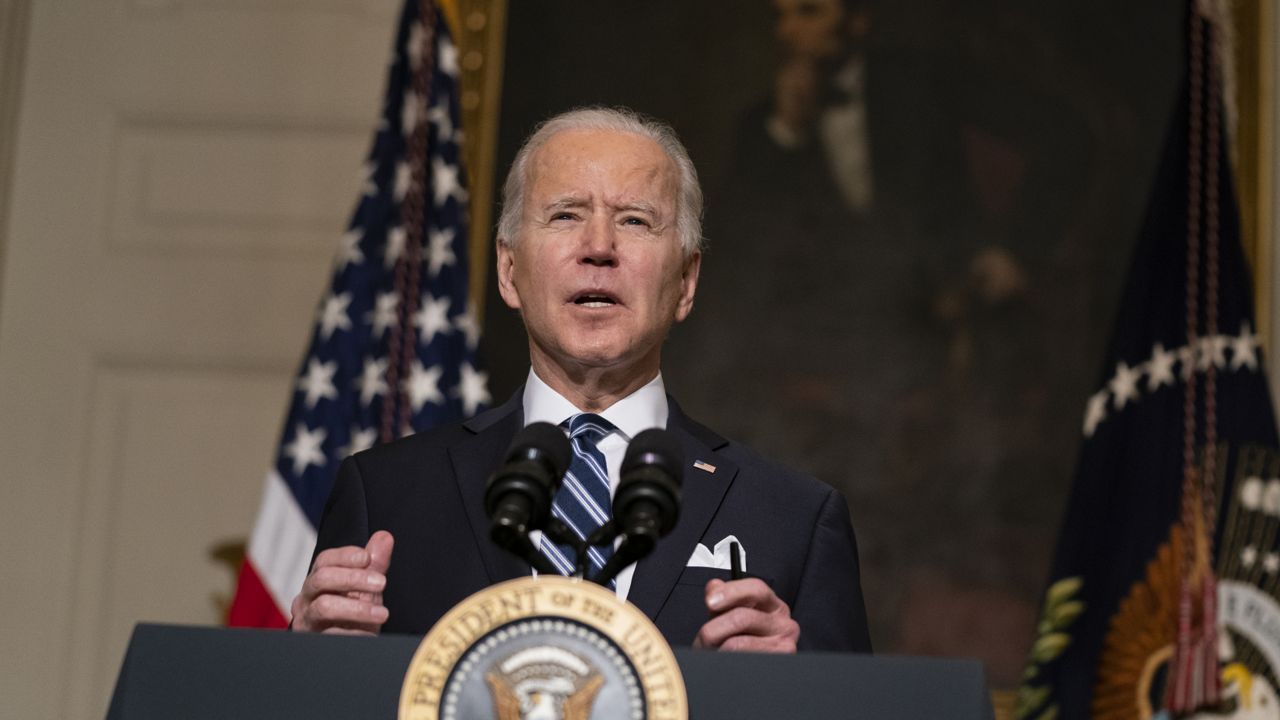

The continued danger from ISIS was not lost on Biden, who said in a speech in late August that the United States will continue to hunt down terrorists, wherever they may be. But he stressed that addressing terrorism meant bringing the fight int the 21st century, and ending the ground war in Afghanistan.

“To those who wish America harm, to those that engage in terrorism against us and our allies, know this: The United States will never rest,” Biden said in a passionate speech from the White House, an echo of his speech delivered 20 years earlier from the Senate floor. “We will not forgive. We will not forget. We will hunt you down to the ends of the Earth, and you will pay the ultimate price.”

“The fundamental obligation of a President, in my opinion, is to defend and protect America — not against threats of 2001, but against the threats of 2021 and tomorrow,” he later added.

And so, two decades after voting to send troops to Afghanistan, Biden solemnly brought the last mission home — but a new kind of war on terror may soon begin.