At 85, Dr. Gwen Gentile has spent her entire career helping women not get pregnant.

In 1967, not long after graduating from Temple University’s medical school, Gentile got a job with The Population Council, a nonprofit that conducts research to address critical health and development issues.

Their work also allows couples to plan their families and chart their futures. During the early 1960s, The Population Council was testing the first ever contraceptive implant. Gentile volunteered to be their first human patient.

Speaking with NY1 recently, Gentile rolled up her sleeves to show the implant still lodged in her right arm more than sixty years later.

“There it is.” Gentile said. “I wouldn’t put it in anybody else if I hadn’t used it first.”

What You Need To Know

- Doctors who perform abortions generally do not sit down for television interviews, as speaking publicly can make them targets of anti-abortion activism and even violence

- But with the U.S. Supreme Court reportedly poised to overturn Roe v. Wade, two veteran New York City doctors decided to break their silence in exclusive interviews with NY1

- Dr. Eddie Mandeville, an OB-GYN who worked at Harlem Hospital in Manhattan for about 15 years and then in private practice in Queens, has a lot in common with Dr. Gwen Gentile, who in her 80s still works at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn.

- Both doctors remember crowded maternity wards during the 1960s filled with girls and women who had miscarriages after an abortion was performed to try to end their pregnancies.

Gentile is proud of her record as it relates to contraception, including her career helping girls and women end unwanted pregnancies. She remembers when abortion was illegal and has vivid memories of what she calls a “battlefield” in hospitals.

The history of birth control dates back hundreds of years, as does the history of terminating pregnancies. And reproductive rights have always been an emotional issue drawn along religious, ethical, moral, and political lines.

Dr. Eddie Mandeville, an OB-GYN who worked at Harlem Hospital in Manhattan for about 15 years and then in private practice in Queens, has a lot in common with Gentile, who in her 80s still works at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn.

Both doctors remember crowded maternity wards during the 1960s filled with girls and women who had miscarriages after an abortion was performed to try to end their pregnancies.

“We saw women who had infections. We saw women who had to have hysterectomies,” Mandeville said. “We saw a couple of women die.”

Fresh out of med school in the late 1960s, Mandeville dreamed of delivering babies and making families happy. But in 1967, he instead found himself in the middle of a nightmarish medical crisis when girls and women were desperate and determined to end their pregnancies.

Decades later, Mandeville is still haunted by what he saw.

“When you gotta go downstairs as a young intern who came to do what you wanted to do, and you have to go downstairs with your senior doctor and tell two kids, a husband and a sister that their loved one is not coming home. It changes your view.” Mandeville said with tears in his eyes.

“And It didn’t have to happen,” he added

But in the years before Roe v. Wade, it was happening. Everywhere.

“I never saw the traditional metaphor of a coat hanger. I did see catheters. However, we would see standard red catheters that the abortionists would infuse with a toxic substance in order to destroy the pregnancy, typically Lysol,” Mandeville said.

Before Roe v. Wade, those performing abortions often used Lysol to cause a miscarriage. It’s something Gentile remembers all too well.

“The Lysol douches, which women used, and we saw them frequently, the catheters still in the vagina that had been used to thread up into the uterus by the quote doctors,” Gentile recalled. “And the Lysol would go through the, you know, go to get into the uterus, you know, get rid of the pregnancy, but it would also get in the bloodstream. And these women would develop — if they had a big enough dose of Lysol — would develop kidney failure.”

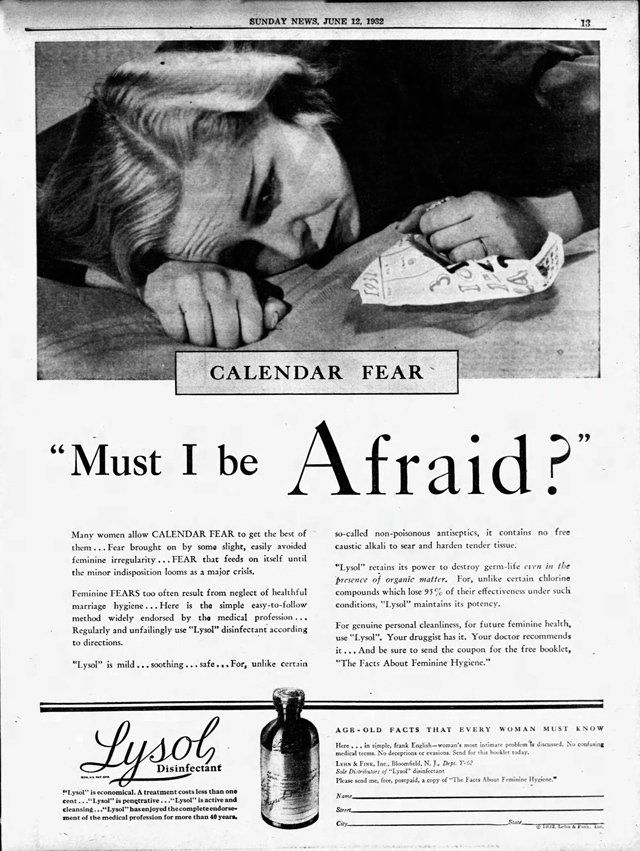

As incredulous as this sounds, NY1 found these ‘vintage’ ads by Lysol online with references to “feminine hygiene” encouraging women to “douche regularly” with the disinfectant, which was first manufactured in 1889. There were also subtle references to use it after unprotected sex.

One ad titled “But I broke through it” includes a short passage about love and close companionship. It encourages women to “follow to the letter” doctor’s advice and use Lysol for “douching”.

When NY1 showed Gentile the ads, she was stunned by what she saw. She had never seen them, but she did see the end result.

“Approved germ killer approved, uh, pregnancy killer too. Yeah. Approved woman killer.” Gentile said while looking at the disturbing ads.

“As a global leader in health and hygiene products, we must be clear that under no circumstances should our disinfectant products be used or administered into the human body (through injection, ingestion, or any other means),” Lysol’s parent company Reckitt said in a statement. “As with all products, our disinfectant and hygiene products should only be used as intended and in line with usage guidelines. Please read the label and safety information. Consumer safety is our number 1 priority at Lysol, and we would like to stress the importance of following the guidelines for safe usage of any product prior to use.”

As Gentile stands outside of Kings County Hospital, she said she’s still haunted by what happened inside the “C” building during the 1960s.

Back then, she was a young doctor, often exhausted after working 100 hours a week inside a 32 bed ward with anguished women having miscarriages.

She describes her working conditions as a battlefield where nurses called the police regularly.

“Abortion was illegal. It was illegal. It was absolutely illegal,” Gentile said.

“So the police would be there all the time and they’d be in the wards and they’d be, they’d be interrogating the ladies,” she explained. “‘You are a murderer. You murdered your baby. I need to know you are going to get prosecuted. You may go to jail. I need to know who did this to you.’”

Mandeville saw police inside maternity wards at Harlem Hospital during this period, as well.

“They would browbeat, they would intimidate. They would threaten, they would charge them with murder,” Mandeville said. “And the tacit part, the part that I’m ashamed of is that we, as doctors, wouldn’t stop it because a lot of times we thought, given the circumstances and watching women die, that they might be better off not having had this termination attempt at the hands of a local butcher.”

“So I often say that we as MDs were somewhat complicit in that intimidation. And it says to me that what we might be facing in this country is a system that’s going to be again.” Mandeville added.

After New York legalized abortion in 1970, Mandeville said, the chaos in maternity wards with women suffering from botched abortions stopped immediately.

Today, more than a dozen states have restricted access to abortions.

Florida, Arizona, Kentucky, Idaho, South Dakota, Wyoming, Louisiana, Arkansas, Montana, South Carolina, and Tennessee.

Oklahoma and Texas have the most restrictive abortion bans in the United States, essentially deputizing citizens to sue abortion clinics and individuals by offering a cash reward of $10,000 if they can prove an abortion has occurred.

Mandeville believes the bans show history is repeating itself as women will now have to leave their home states to receive care.

Just days after the leak of the draft opinion of the Supreme Court’s potential ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade, on. May 2, 2022, state Attorney General Letitia James and Governor Kathy Hochul both pledged to set up a fund for women across the country to fly to New York to safely terminate their pregnancies.

In 1970, three years before Roe v. Wade, New York became the second state to legalize abortion after Hawaii.

“There were plane loads of women coming to New York.” Mandeville recalled.

“I am not an ethicist. I’m not a theologian. For over 50 years, I’ve taken good care of my patients. And if you don’t believe me ask them, I respect the other side for their philosophical and their ethical views. But one thing I am sure of is if the way I’ve taken care of my patients overall this time is going to cause me to burn in hell eternally. God will decide that. And not them. How dare they think that they can make that decision,” Mandeville said with anger.

“I cry.” Gentile said with tears streaming down her cheeks. “My whole career has been to help women not get pregnant.”

When asked her response to Americans who have fought so hard to reverse Roe v. Wade, Gentile says she understands them.

“Yes. I understand them. They have principles. They have concerns. I understand them. I don’t think they’re evil.” she said. “I don’t care what they think about us.”

“I’m just sad that they don’t understand what it’s like to be that woman who needs not to be pregnant with no leeway, a rapist with a knife at her throat, having been made to have sex,” Gentile added. “That is just as bad as anything I can think of.”