For the better part of the last 170 years, the Democratic Party and the Republican Party have been the prominent voices in American politics.

But in the 2024 cycle, a pair of new national third parties, the No Labels Party and the Forward Party, are hoping to buck trends, asking Americans to throw in their lot for an approach that Americans may be more willing to buy into in a time of hyperpartisanship.

It’s not unusual for third parties to break into the public consciousness. Some, like Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive (or “Bull Moose”) Party or Texas businessman Ross Perot’s Reform Party, ride a central candidate’s cult of personality before flaming out.

Others have stuck around for a while longer, with popularity waxing and waning as the years go by.

The left-wing Green Party, which once backed consumer activist Ralph Nader and retired physician Jill Stein, for instance, has fallen off of some state ballots for not gaining enough votes during elections; the right-wing Libertarian Party, on the other hand, gained its largest-ever share of popular votes in the 2016 presidential election, behind former New Mexico Governor Gary Johnson.

Across the country, there are more than 200 recognized state-level political parties, about half of which are affiliated with either the Democratic or Republican parties.

The others are a potpourri of parties — at least a dozen with some variation on “independent” to their names; nearly as many “Constitution” parties; at least as many organized around working families and labor; some Reform Party holdouts; a handful of cannabis-centric parties, including two in Minnesota.

There are also a few less-serious one-offs, like the Pizza Party and the Pirate Party, both in Massachusetts, and a few more serious solo parties, like the Aloha ʻĀina Party, which seeks to make right the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1893.

Like much of Georgia, most of Texas is comfortably considered a GOP stronghold — and what few seats aren’t held by Republicans are held by Democrats.

Linda Curtis, of the League of Independent Voters of Texas, has been working to make third parties a part of the actual conversation since Ross Perot took the country by storm in the mid-1990s with his Reform Party presidential run.

The league itself was founded in 2013, and is oriented toward “herding the cats known as independent voters,” Curtis said.

“And getting them more options to vote for — including independent candidates, not just those that are aligned with a particular party,” Curtis added.

She said that the current problem with third parties, and the independent movement in general, is a lack of vision and cohesion. The movement isn’t so much a “big tent” so much as it is a festival, with dozens of smaller “tents” butting up against one another, competing for attention and allegiance.

“The independent movement, just as all electoral movements, is driven by who is willing to fund what. And so there’s money around to push for some new voting tools … and that’s fine and good,” Curtis said. “But do you think the average person out there — even people who identify as an independent voter in some manner, really thinks much about gerrymandering and things like that? They should, but they don’t.”

Instead, they’re concerned with their day-to-day living — and Curtis says that’s where the disconnect is between the independent parties seeking to capture big ideas and the voters who don’t want to have to worry about the next paycheck, or how much water they’ll have next month.

“We’re trying to not make assumptions about where’s the sweet spot for organizing independent voters. For forever, since the Perot movement, we just decided we’re not going to talk about guns and abortion,” Curtis said. “But this is like 30 years later.”

That said, Curtis thinks that the Forward Party is a good example of local-level organizing.

“Everybody thinks that you have to have a leader to entice people to get engaged … I think what plagues the independent movement is that thought,” she said.

Meanwhile, in some small towns and local races, everyone knows, or has an opinion about, the local sheriff, or the school boards, or even the mayor. And in those races, candidates can’t necessarily come in with all of the answers in hand.

“You have to learn how to listen and really understand what people are trying to get at,” Curtis said.

Meanwhile, Curtis says she doesn’t care much for the No Labels strategy.

"I’m not dissing anybody who wants to get in the game and mix things up … (but) I don’t go for this ‘moderation’ business,” Curtis said. “They think that there’s some middle-ground to take, and I don’t think politics is working that way anymore.”

Unity tickets, such as the one proposed by No Labels, have never really come together, she said. To wit, as Seth Masket wrote in the Los Angeles Times, these tickets are floated just about every four years — from Unite America in 2020, to Americans Elect in 2012, to Unity08 “trying to make Sam Nunn/Michael Bloomberg a thing,” to even the idea of a Kerry/McCain ticket in 2004.”

One of the few times a national unity ticket did work was in 1864, amid the Civil War, when Republican Abraham Lincoln tapped Democrat Andrew Johnson in a bid for unity between the parties amid the literal most-divided time in United States history.

Bernard Tamas, an associate professor at Valdosta State University, told Spectrum News that third parties are most primed to make a difference when polarization is at its height.

“So there was a huge amount of room for what we could refer to as ‘the center,’ but there were also issues that were being ignored,” Tamas said. “So these parties could galvanize the public” on government corruption and labor-related issues. “They were able to tap into some serious anger, they could come in and crash the system and at least force the major parties to respond.”

Third parties, he said, generally need one of two things to make a dent: they need an issue that galvanizes voters, or they need to deliver a message that’s very different than voters have heard before. They also need resources, which are increasingly hard to come by in America's modern political landscape.

“If you look at Perot, his genius was to figure out how to express things in a way that was different than what people were hearing at the time — that sounded folksy and practical,” Tamas said.

And though Perot’s positions weren’t all that radical, Republicans in 1992 were happy to adopt the ones with the best political value, like his opposition to NAFTA and internationalist policies and his attacks on President Bill Clinton’s health care plan. (It helped that his policies didn’t mention a handful of Republican third-rails, such as guns, abortion or free trade.)

But right now, Tamas said, there’s nothing to galvanize on that the major parties haven’t already assumed control of, like the Democrats staking ground on abortion in the aftermath of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade.

So he’s finding it hard to give the Forward Party — which he found didn’t have an anchor issue to build around — or No Labels — where he similarly doesn’t see a driving argument — much of a shot.

“As a third party, it’s very hard to be both on the inside and to be a rebellion at the same time,” Tamas said of No Labels. Further, the argument that they’re trying to split between extremes doesn’t hold much water to him either.

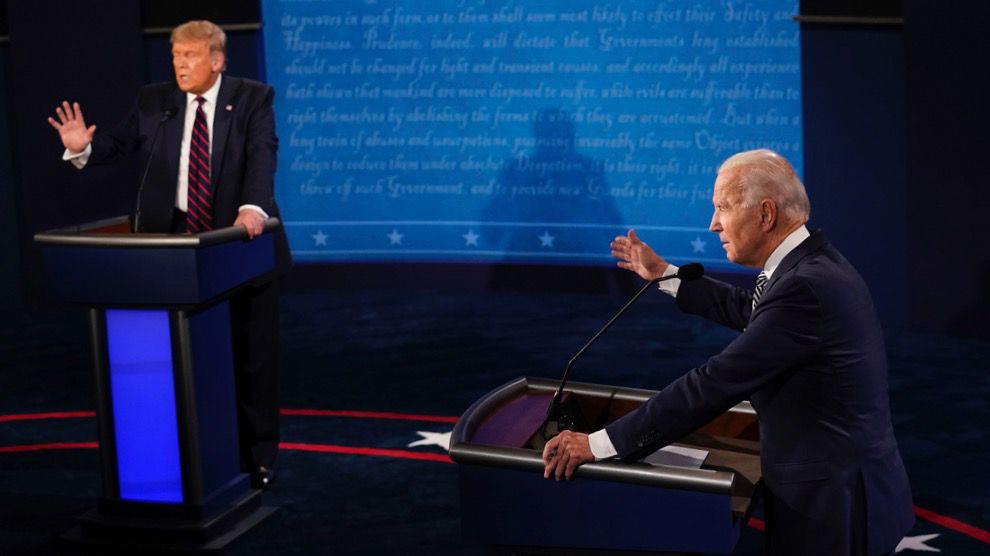

“Part of the problem is that Joe Biden will almost definitely be the Democratic nominee, and Joe Biden is a moderate. If Bernie Sanders was president, or going to be the nominee, it might make sense … and on the Republican side, we have no idea who’s going to be the nominee, so they’re trying to galvanize against the hypothetical.

President Biden, a man of many aphorisms, attributes a line oft-used in his speeches to his father: "Joey, don't compare me to the Almighty, compare me to the alternative."

For the last three years or so, the alternative has been the far-right "MAGA Republicans," as Biden calls them, and former President Donald Trump.

But, when asked by reporters what the White House thinks of nascent third-party upstarts, White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre sidestepped — while comparing Republican priorities ("They want to cut key programs") to Biden's priorites ("To build an economy that doesn't leave anybody behind") before tying her response in a neat bow.

"He's going to continue to build an economy from the bottom-up, middle-out," Jean-Pierre said at a recent White House press briefing. "I'm not going to speak to specifically to 2024, but this is a president who understands what it's like to make sure that we have put the American people first, and that's what he's going to continue to do."

But, as Tamas notes, some states are so closely divided that they could potentially play a spoiler role in 2024. Depending on how the votes fall, they may shift the election to the Republican Party.

"What I don't see is any evidence that that playing spoiler on the presidential election will lead to any policy changes," he said, noting that Ralph Nader's campaign sunk Al Gore's presidential hopes in Florida, leading to a George W. Bush win in 2000 — and, ultimately, led to voters fleeing the Green Party.

On May 1, No Labels tried to get ahead of this argument with a statement entitled "Donald Trump Should Never Again Be President" signed by Founding Chair and one-time vice presidential candiate Joe Lieberman and national co-chair Benjamin Chavis Jr.

"We don’t believe there is any 'equivalency' between President Biden and former President Trump, who is a uniquely divisive force in our politics and who sought to disrupt the peaceful transfer of power after he lost the 2020 election," the statement said. "But we reject the notion that No Labels’ 2024 presidential insurance project would inevitably help former President Trump’s electoral prospects if he were the Republican nominee."

The statement goes on to say that its polling shows the majority of Americans don't want a 2020 presidential rematch — and that if the Democrats and the GOP "continue ignoring the clear will of most Americans, No Labels will have a ballot line in every state ready to nominate a potential Unity presidential ticket.

But the path to making a difference, Tamas said, has more often involved making a big splash, rallying the public around a cause to force policy changes, rather than crashing elections.

"Running some spoiler presidential candidate is not going to is not going to do much of anything other than get people to hate your party," Tamas said.