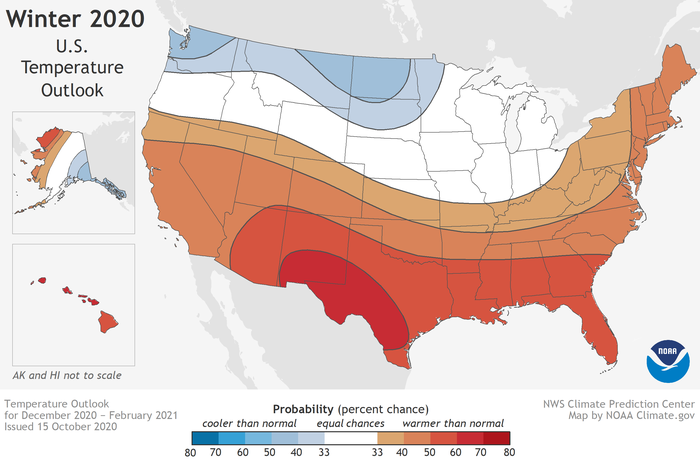

If the 2020 winter weather outlook released this week is anything to go off of, you’ll really want to bundle up around the Great Lakes.

Fair warning, Ohio, Wisconsin, Kentucky and our friends across the Great Lakes: It could be a real doozy of a winter.

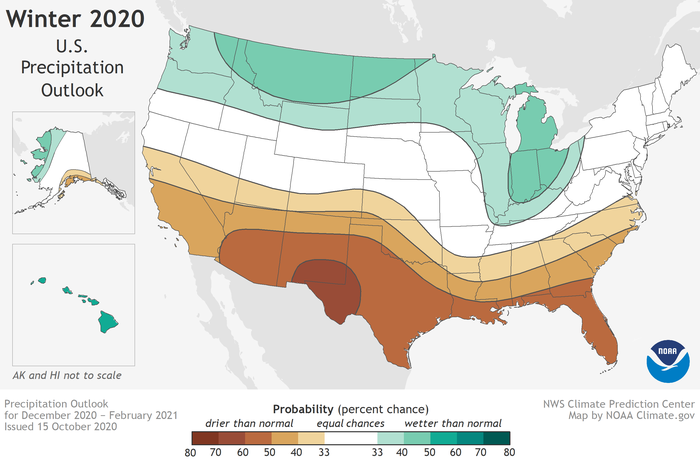

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) winter weather outlook, released Thursday, highlights much of the northern tier of the country as having a greater than average chance at both a colder and wetter (therefore snowier) winter season.

The outlook is for the months of December, January and February.

On the flip side, the southern tier of the country trends warmer and drier, which could have negative impacts on the ongoing drought across the Four Corners and Southwest, including California.

NOAA's overall U.S. winter outlook closely follows the traditional domino effect caused by La Niña, or cooler-than-average sea-surface temperatures in the central Pacific Ocean.

When it comes to broad-brushed seasonal forecasts, one of the first things long-range forecasters will look at is the ENSO cycle, or sea-surface temperatures in the central Pacific Ocean.

When the waters of the central Pacific are warmer-than-average, it's known as El Niño. When it's colder-than-average, like what we've seen and anticipate for much of the winter, it's known as La Niña.

The reason these ocean temperatures are so closely monitored is that a variation will create a series of effects on global weather, including here in the U.S. The Pacific Ocean is (by far) the world's largest ocean, so its sea-surface temperature variability has an outsized impact on the rest of the world's weather.

Meteorologist Shelly Lindblade has a detailed look at La Niña's typical impact on U.S. winters here, and it closely correlates with the NOAA winter weather outlook.

The northernmost (Polar) jet stream - the narrow ribbon of strong winds that dictates much of our weather - is often highly variable during a La Niña winter. That can mean frequent blasts of colder air, mainly targeting the northern third of the country.

Along with those cold blasts come frequent blasts of snow, and lake-effect snow can increase as well due to more cold air rushing over the relatively warm waters of the Great Lakes.

“With La Niña well established and expected to persist through the upcoming 2020 winter season, we anticipate the typical, cooler, wetter North, and warmer, drier South, as the most likely outcome of winter weather that the U.S. will experience this year,” said Mike Halpert, Deputy Director of NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

The winter months are California’s wet season. From November through March, almost all of central and southern California’s annual rain and mountain snow falls, making that moisture extra critical for this relatively dry part of the country.

It doesn’t appear, based on the outlook, that much relief is on the way for the parched region this winter.

"The ongoing La Niña is expected to expand and intensify drought across the southern and central Plains, eastern Gulf Coast, and in California during the months ahead," the NOAA outlook stated.

California and the Southwest typically see bigger rain and snow events during an El Niño winter, when the subtropical jet stream gets an extra boost thanks to warmer sea-surface temperatures in the central Pacific. In a La Niña winter, high pressure usually boosts temperatures and steers moisture into the Pacific Northwest.

NOAA bases their seasonal outlooks on general trends over the course of a season, but there are several key caveats to keep in mind with these types of forecasts.

First of all, a seasonal outlook is an overview for a long period over a wide chunk of land, so there will still be big changes on a day-to-day basis. For example: If the south is trending warmer-than-average this winter, that doesn't mean you'll feel warm every day in December, January and February.

Also, seasonal and long-range forecasting is still in its infancy and an inexact science, so take these predictions with a grain of salt.