Over 12 years, New York City saw a short-lived soda ban, some tax increases, and a spike in stop-and-frisk.

Michael Bloomberg may be a Democratic presidential candidate, but his time as mayor was more complicated. He backed both liberal and conservative measures.

Here's a look back at Bloomberg's record as mayor:

Public Health | Policing | Homelessness | Term Limit Changes | Climate Change | The Economy | Education | Political Parties

Smoking Bans and Calorie Counts

Bloomberg said he was saving lives and increasing life expectancy. His critics claim he created a nanny state.

Well, we know New Yorkers now have fewer places to smoke because of Bloomberg.

In late 2002, under Bloomberg's watch, New York City banned smoking in restaurants and bars. He followed that up in February 2011, when he signed a bill barring people from lighting up in city parks, on beaches and boardwalks, and in pedestrian plazas like Times Square. He and supporters said the smoking bans protected people from secondhand smoke and cut down on litter from cigarette butts. People who violated the orders were subject to fines.

Bloomberg also set his sights on giving New Yorkers healthier dining options. Restaurants were banned from using trans fats starting in 2005, and the city in 2008 required calorie counts for chain restaurant menus.

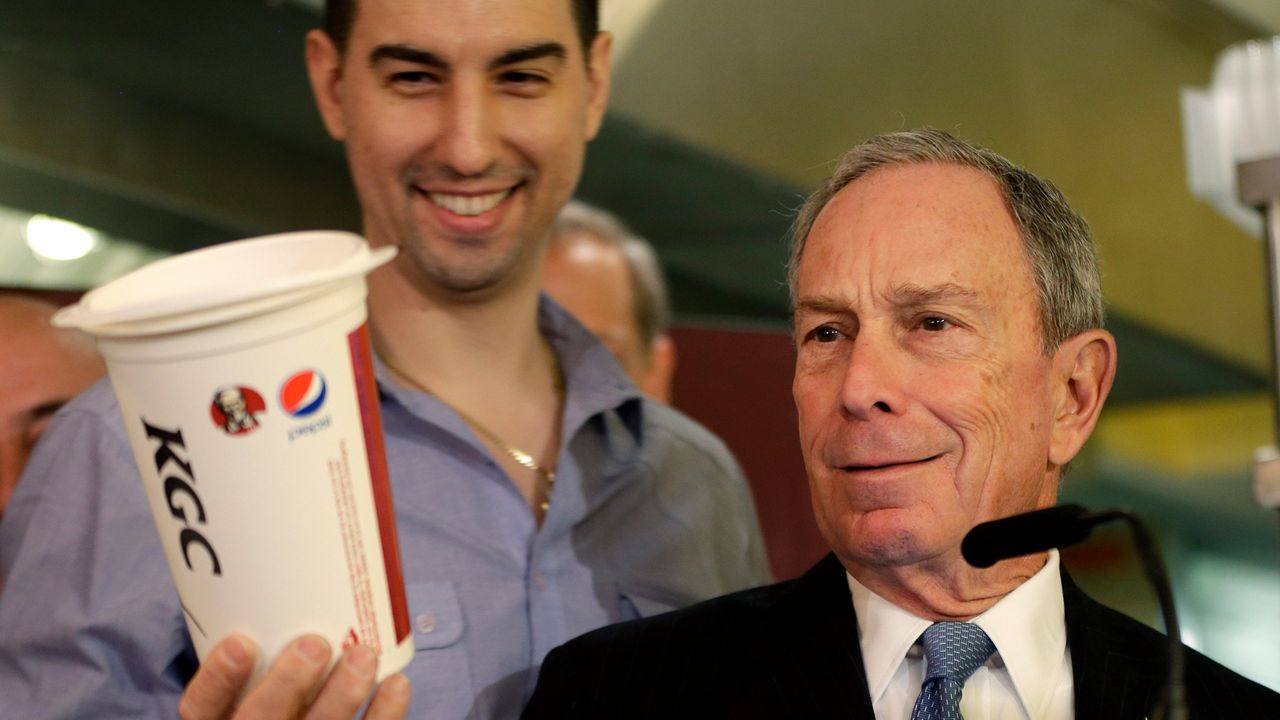

Soda Ban

In 2010, he called on New York state lawmakers to adopt a penny-per-ounce tax on sweetened soda. He said that could raise nearly $1 billion a year. The measure didn't pass in the state legislature.

The mayor was defeated again two years later, when a court struck down a ban on large sugary beverages. The judge wrote the regulations were "fraught with arbitrary and capricious consequences," noting that they would apply to some but not all food establishments and excluded some high-calorie drinks packed with sugar.

Plaintiffs, including restaurant and theater owners and the soft drink industry, hailed the death of the soda ban as a victory for small businesses and entrepreneurs. New York City's appeal was rejected in June 2014, when the state Court of Appeals ruled that the city's board of health overstepped its authority when it approved the ban.

Bloomberg pushed for the ban to help fight obesity in the city. But many New Yorkers never liked the directive, saying it gave the government too much power over their personal matters and was an attempt to trample on their rights. The mayor countered that the litigation was pushed by special interests.

Supporting Stop-and-Frisk

One of the biggest controversies that follows Bloomberg on the campaign trail is his defense of stop-and-frisk.

As soon as Bloomberg took office in 2002, the number of stops by the NYPD skyrocketed, climbing to its highest point in 2011: 685,724.

Stop-and-frisk incidents began to decrease as a class action lawsuit against the practice made its way through court. In 2013, a judge ruled the practice unconstitutional and said it disproportionately affected black and Hispanic New Yorkers.

But it wasn't until November 2019, as he was seriously considering a run for president, that Bloomberg apologized for stop-and-frisk. Bloomberg's reversal, six years after the ruling, made headlines for a man not known for admitting errors. In fact, he defended the policy in January 2019. Critics panned his apology as conveniently timed given that he was expected to launch a presidential bid as a Democrat, a party increasingly rejecting more aggressive policing tactics.

Supporting the Surveillance of Muslims

A 2012 Associated Press investigation of police intelligence reports found that the city police department had for years monitored mosques, Muslim neighborhoods, and students. Among the findings: the NYPD sent an undercover officer with students from City College on a whitewater rafting trip, monitored online activity of Muslim students, and fixed cameras to light poles to surveil mosques.

Bloomberg came to the department's defense. The mayor argued the NYPD was keeping the city safe, but the investigation found the surveillance occurred despite no links to criminal or terrorism activity.

Spike in Marijuana Enforcement

While it took years after he left office for the political tide to shift towards leniency for low-level marijuana possession, Bloomberg's NYPD arrested tens of thousands of people for possessing the drug. According to data from the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, in 2008 alone there were 40,383 marijuana possession arrests in New York City, more than the sum of the previous three mayoral administrations combined.

A Drop in Crime

While he backed some aggressive policing policies, Bloomberg earned praise for the city's crime rate continuing to fall under his watch. The number of murders in the city peaked in 1990, at 2,245. By the end of 2012, New York's rate of 3.8 homicides per 100,000 residents was far lower than many other major cities, such as Baltimore, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Chicago, and Detroit. In 2013, Bloomberg's last year in office, the total number of homicides in New York City was about 330.

Back in 2004, Bloomberg set a goal of cutting street homelessness and the shelter population by two-thirds. Instead, the shelter population actually increased during his time as mayor. According to the Coalition for the Homeless, over 48,000 people were in city shelters by the time Bloomberg left office, an increase of more than 15,000 compared to January 2002, when he began his first term.

The billionaire mayor was, at times, seen as insensitive to the homeless. In February 2013, he was criticized for saying "nobody is sleeping on the streets." In fact, by the city's own count, more than 3,200 homeless people were on the streets in January 2012.

The mayor's comment came at a time of intense scrutiny over the city's homeless policies. A week before his comments, a state appellate court sided with the City Council in its challenge to a Bloomberg administration policy that required single adults prove they had no other alternative when seeking access to a homeless shelter. City Hall also faced criticism for turning families away from shelters on cold winter nights.

"We're trying to do what we're supposed to do: make sure that people who need services get those services, and that people who don't need them don't get them," Bloomberg said.

Bloomberg was one of New York City's longest-serving mayors. But the path he took to becoming a three-term mayor was paved with controversy.

In October 2008, a year before the mayoral election, the City Council, by a 29-22 vote, approved Bloomberg's request to extend the two-term limit for city elected officials. Once adamantly opposed to overturning the will of the people, the mayor had argued New York needed his economic expertise so he could lead the city for a third term after the 2008 financial crisis.

"Handling this financial crisis while strengthening essential services, such as education and public safety, is a challenge I want to take on," Bloomberg said in a news conference announcing his term limit request.

Then-City Council Speaker Christine Quinn made a similar argument in defending the council extending term limits, saying New Yorkers needed the opportunity for "consistent leadership." She denied charges that there was a backroom deal.

A Quinnipiac University poll two days before the vote found that 89 percent of voters preferred a referendum, not a council vote, to decide if term limits should be extended beyond two four-year terms. A 2008 Marist College Poll found New Yorkers were divided — 46 percent in favor, 44 against, and 10 percent undecided — when pollsters asked if term limits should be changed for Bloomberg, specifically.

One mayoral candidate, City Comptroller Bill Thompson, denounced Bloomberg's move as an "attempt to undermine democracy in New York City" and to "suspend democracy."

Quinn and others argued the 2009 election would be a referendum on term limits — anyone who had a problem with extending them could simply vote Bloomberg and everyone out of the office. The mayor ended up narrowly winning re-election, by around 78,000 votes (approximately 51 percent of the vote compared to Thompson's roughly 46 percent). It was a closer result than most expected. Some said Bloomberg's bid to stay in office nearly cost him.

Later voters overturned Bloomberg's move, reverting term limits back to two terms.

Reducing Emissions

Since he left office, Bloomberg has been known in part for his political spending and advocacy for reversing climate change.

While at City Hall, Bloomberg released a sustainability plan, plaNYC, which outlined dozens of projects to make a greener New York. Among the goals:

- Reducing the city's greenhouse gas emissions 30 percent by 2030

- Reducing congestion on city streets, in part through congestion pricing

- Improving buses and expanding ferry services to get people out of cars

- Opening hundreds of playgrounds and parks, and planting more trees

- Conserving water and considering new water sources

- Rezoning 21 neighborhoods and creating more housing so more New Yorkers could live closer to mass transit

Not all the objectives were realized, most notably congestion pricing. The mayor tried unsuccessfully to replicate London's system, pushing it in the New York state legislature. He hoped the city's fee would not only raise revenue, but get people out of cars to reduce emissions. Congestion pricing died in the state legislature at that time, but it ended up passing in 2019.

But the city did get some of Bloomberg's proposals, such as opening more parks and switching to cleaner heating fuels.

Preventing Flooding

Bloomberg had one significant climate crisis while he was mayor — and it was the city's biggest: Hurricane Sandy in October 2012. Forty-four people were killed in the city, most of them on Staten Island. Thousands of homes were wrecked on Staten Island and in the Rockaways. Sandy also caused more than $4.7 billion in damages to tracks, tunnels, subway stations, and more than a dozen crossings.

After Sandy, Bloomberg released more than 400 pages of plans and timetables to prevent flooding in future storms, and to fortify New York against rising temperatures and seas. His plans — which included seawalls and storm surge barriers — had an overall price tag north of $10 billion and required $4.5 billion from sources he didn't specify. Strategies to cover the gap are listed, but search "subject to available funding" and it comes up more than a hundred times.

(A June 11, 2013 file photo of Mayor Michael Bloomberg speaking while a map of the projected 2050s 100-year flood plain of New York City is displayed. Seth Wenig/AP).

Coastal protection was crucial, and City Hall underscored its importance with an ambitious deadline: By 2016, "flood protection systems" were to be in place at five spots in the Bronx, Manhattan, and Brooklyn. Costing tens of millions of dollars per location, they would block or divert water surge, whether with moveable panels or something more permanent.

There has been some progress, but major projects have been scaled back and are far behind schedule. To critics, Bloomberg's successor, Bill de Blasio, has also diluted a focused environmental plan. It was about protection in an era of rising seas. Now, it's grown to include social justice in an era of inequality.

Maybe the most noteworthy Bloomberg response to Sandy: Build It Back. In early June 2013, eight months after the storm, his administration created the program. It was supposed to help keep Sandy victims in their homes and neighborhoods, by rebuilding, lifting, and repairing houses to make them storm-resistant as quickly as possible.

None of that happened under Bloomberg. When Bill de Blasio became mayor in 2014, not a single homeowner had received money from Built It Back and no homes were under construction.

A scathing audit by City Comptroller Scott Stringer was released March 31, 2015, examining six months of the program under the Bloomberg administration and eight months under de Blasio. The audit found Built It Back "failed to implement proper controls to ensure the appropriate, prompt and efficient delivery of services to applicants."

The program, which de Blasio is mostly blamed for, has been plagued by building delays, soaring costs, and communication issues.

Vetoing Living Wage Bills

In 2012, Bloomberg vetoed City Council bills to impose wage mandates on some private businesses.

"Those bills — the so-called living and prevailing wage bills — are a throwback to the era when government viewed the private sector as a cash cow to be milked, rather than a garden to be cultivated," the mayor said.

Bloomberg argued that meant, in effect, taxpayers would subsidize private sector salaries; either that, or businesses wouldn't invest in New York City at all.

"I will not sign legislation, no matter how well-intended, that hurts job creation and taxpayers," he said. "The council wants to take revenue from owners and give it to a select group of employees. That's not the way the free market works."

In June 2013, Bloomberg also vetoed a paid sick leave bill the City Council overwhelmingly approved to force businesses with at least 20 employees to provide five paid sick days. Bloomberg had been a longtime opponent of the bill. In his veto message, he said it would increase costs for small businesses.

Bloomberg's tune on wage mandates changed once he ran for president. At a December campaign stop in California, he released new proposals to create economic opportunity for all Americans. Among the ideas: raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2025. The $15 number is popular among Democratic candidates and voters.

"To fight poverty, we need to do something even more basic, and that is raise incomes. And we should start with the most straightforward change: raising the minimum wage," he said.

Increasing Taxes

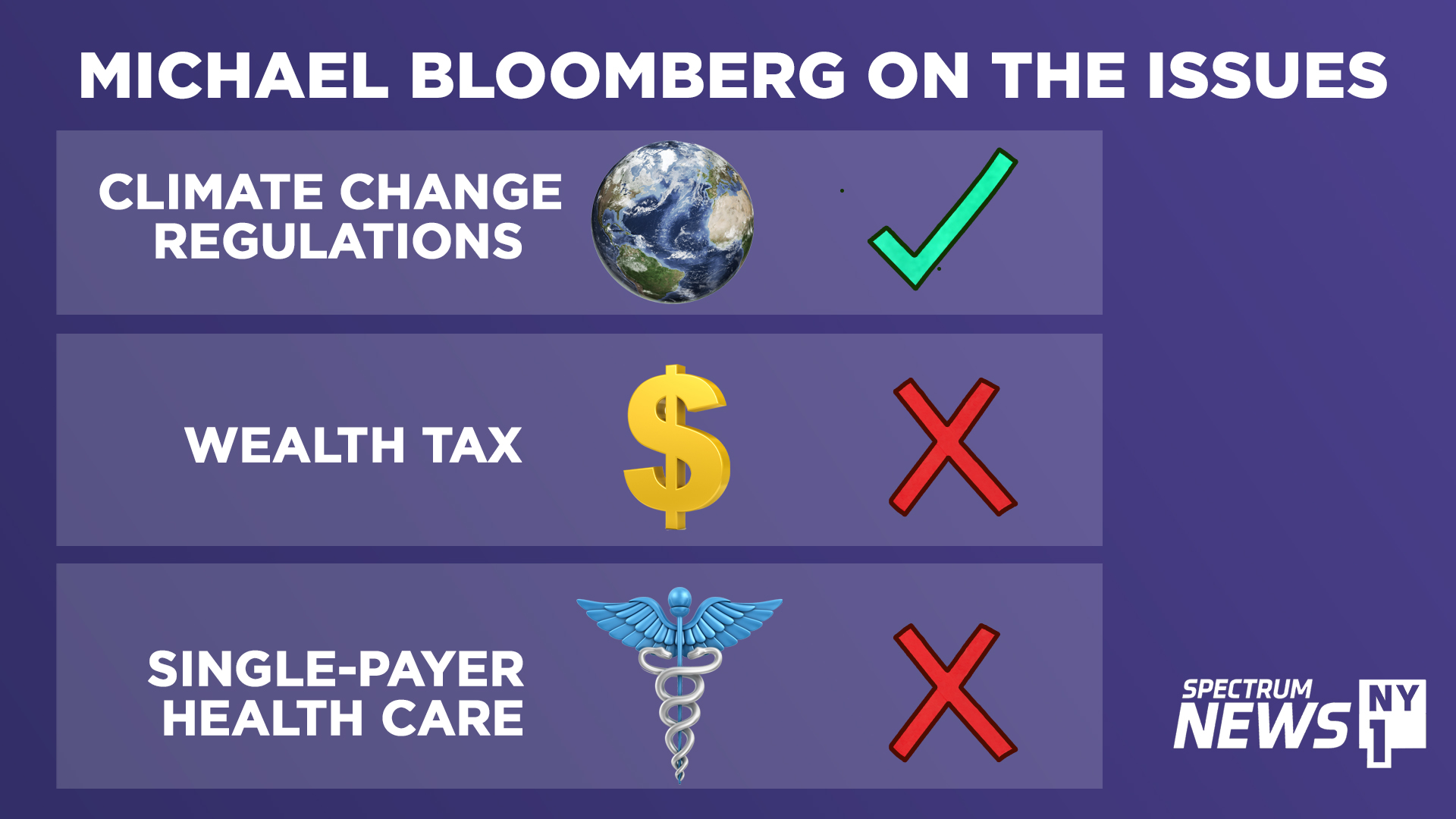

While Bloomberg opened his presidential campaign by advocating for increasing taxes on the wealthy, he hasn't always backed it.

"We cannot drive people and business out of New York. We cannot raise taxes. We will find another way," Bloomberg said during his 2002 inauguration speech.

Eleven months later, that pledge was broken.

In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, a fiscal crisis came along with massive budget deficits. Bloomberg drastically increased property taxes. The following year, he increased the personal income tax rate for higher-income households.

"It is painful, but it is the right thing to do," he said in 2003.

The city faced another recession years later, and Bloomberg increased property taxes again. Then, there were increases to the sales tax and the hotel tax — tax increases that were necessary, he argued.

But as the economy improved, Bloomberg's message seemed to change.

"We could get every billionaire around the world to move here," he said in 2013. "It would be a godsend."

And he made it clear that he did not support additional taxes on the wealthy.

"If you want to drive out the 1 percent of the people that pay roughly 50 percent of the taxes, or the 10 percent of the people that pay 70-odd percent of the taxes, that's as good a strategy as I know," he said in 2012. "It is about a dumb a policy as I can think of."

He even repeated that idea earlier in 2019, in New Hampshire.

"If you want to look at a system that's non-capitalistic, just take a look at what was perhaps the wealthiest country in the world, and today, people are starving to death," Bloomberg said. "It's called Venezuela."

In his presidential stump speech at the start of his 2020 campaign, the former mayor said he wanted to tax wealthier people. But when asked specifically about a wealth tax, Bloomberg seemed to retreat to his old footing:

"A wealth tax has been tried in a number of countries, I think France the last time," he said. "It just doesn't work.

Bloomberg's team told NY1 in late November that the Democrat will release a detailed plan on how as president he would tax the wealthy more. It's unclear when we will see those details.

Before Bloomberg was mayor, New York City schools were controlled through the old Board of Education. The board had seven members. The mayor selected two and each borough president had an appointee. But no one person was accountable for the performance of the school system. But in June 2002, Bloomberg lobbied the state legislature to pass a bill giving the mayor control of the schools.

Bloomberg's most dramatic reform involved closing schools. He closed 150 schools for poor performances, and opened hundreds of small schools to replace them. The decisions enraged some parents, advocates, the teachers' union, and elected officials, including then-Public Advocate Bill de Blasio, who has since pulled the plug on some schools himself as mayor. In response, Bloomberg pointed to improved graduation rates and test scores.

In his bid to improve schools, Bloomberg embraced holding them to stricter standards and giving each school a letter grade based on their test scores. The former mayor believed in measuring student growth, teacher ability and school performance by standardized test scores, which critics charged undermined the quality of education. Test scores have continued to go up under de Blasio, despite focusing less on standardized testing.

Bloomberg had required all students who failed the state English and math tests go to summer school. Students then had to pass a test at the end of the session to move on to the next grade. Bloomberg touted his controversial policy as "the end of social promotion," arguing it was a disservice to pass students who hadn't mastered the material. But in 2014, state lawmakers forbid using test scores as the sole factor for determining promotion or retention, and de Blasio revamped the city's policy, leaving it up to teachers and administrators.

Bloomberg has also been a proponent of the school choice movement, calling for an enrollment system less tied to geography. In 2017, an Associated Press analysis found that Bloomberg donated $1.8 million to ballot measures and political action committees that focused primarily on school choice between 2007 and 2017. His support is largely responsible for the hundreds of charter schools operating in New York City today, serving more than 126,000 students.

Bloomberg has a complicated political party identity. Now a Democrat, he was never elected mayor as a member of that party. But he was elected as a Republican.

In 2001, then-candidate Bloomberg had just switched to the Republican Party from the Democratic Party. Mayor Rudy Giuliani pointed to the billionaire businessman's success in creating the Bloomberg financial news network, and said Bloomberg's status as a non-politician with a varied background would help him lead the city.

"Rudy, I can promise you that I will not take us back. I will take what you've done and use that as a base," Bloomberg said at the endorsement news conference with Giuliani. "Four years from now, this city will be even better than you've given it to us."

Bloomberg was ultimately elected to three terms as New York City mayor — twice as a Republican in 2001 and 2005 and as an independent for his third term. Nine years later, in 2018, he returned to the Democrats as he considered a presidential run. Bloomberg's team trumpeted his role in helping Democrats win control of the House of Representatives that year. He poured tens of millions of dollars into 24 House races. Democrats won all but three of them.

But that doesn't tell the full story. He has a history of donating to GOP candidates, including as recently as 2018.

That year, Democrat Liuba Grechen Shirley waged a spirited challenge against Long Island Congressman Pete King, a longtime Bloomberg ally. Bloomberg backed King, hosting a fundraiser for him. King won by six points.

Bloomberg also backed another longtime Republican ally, Staten Island Congressman Dan Donovan, in his unsuccessful re-election bid against Democrat Max Rose. Rose endorsed Bloomberg's presidential run in January.

As mayor, Bloomberg endorsed President George W. Bush for re-election over Democrat John Kerry.

"The president deserves our support," he said in 2004.

Bloomberg helped Republicans maintain their slim majority in the state Senate, where they successfully blocked progressive legislation for years.

And as Democrats seek to win control of the U.S. Senate, it's notable how many Republican senators Bloomberg has backed in recent years. Some of those senators include:

- Pennsylvania Sen. Pat Toomey

- Late-Arizona Sen. John McCain

- Maine Sen. Susan Collins

- Former Illinois Sen. Mark Kirk

- Former Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch, among others.

In a statement, a Bloomberg spokesman said, "Mike's contributions to Democrats...overwhelmingly outstrip his support for the rare Republicans who put country over party and be on the right side of history. But as Mayor when New York City was pushing Republicans for things like 9/11 recovery support and sensible gun reforms, he sometimes supported people who helped New Yorkers even when he didn't share their values."

------

This story includes reporting from Courtney Gross, Josh Robin, Bobby Cuza, Gloria Pazmino, and Amanda Farinacci.

------

ADDITIONAL BLOOMBERG 2020 COVERAGE

Bloomberg Pours Resources Into Presidential Campaign at Unprecedented Rate

Bloomberg's Record Scrutinized as He Unveils Proposals to Reduce Incarceration

Bloomberg Apologized for Stop-and-Frisk at a Church Visit. What Does the Pastor Think About It?

Bloomberg Buys Over $30M in Campaign Ads

'The Many Lives of Michael Bloomberg'

------

Looking for an easy way to learn about the issues affecting New York City?

Listen to our "Off Topic/On Politics" podcast: Apple Podcasts | Google Play | Spotify | iHeartRadio | Stitcher | RSS