By now you’ve likely seen Spot run, sit and scout the inside of a collapsed parking garage in lower Manhattan.

The robot "digi-dog" has returned to New York City, rejoining the police force after its contract was first severed in 2021 under criticism from lawmakers, as Mayor Eric Adams makes technology a centerpiece of his vision for the city.

But have you heard of K5?

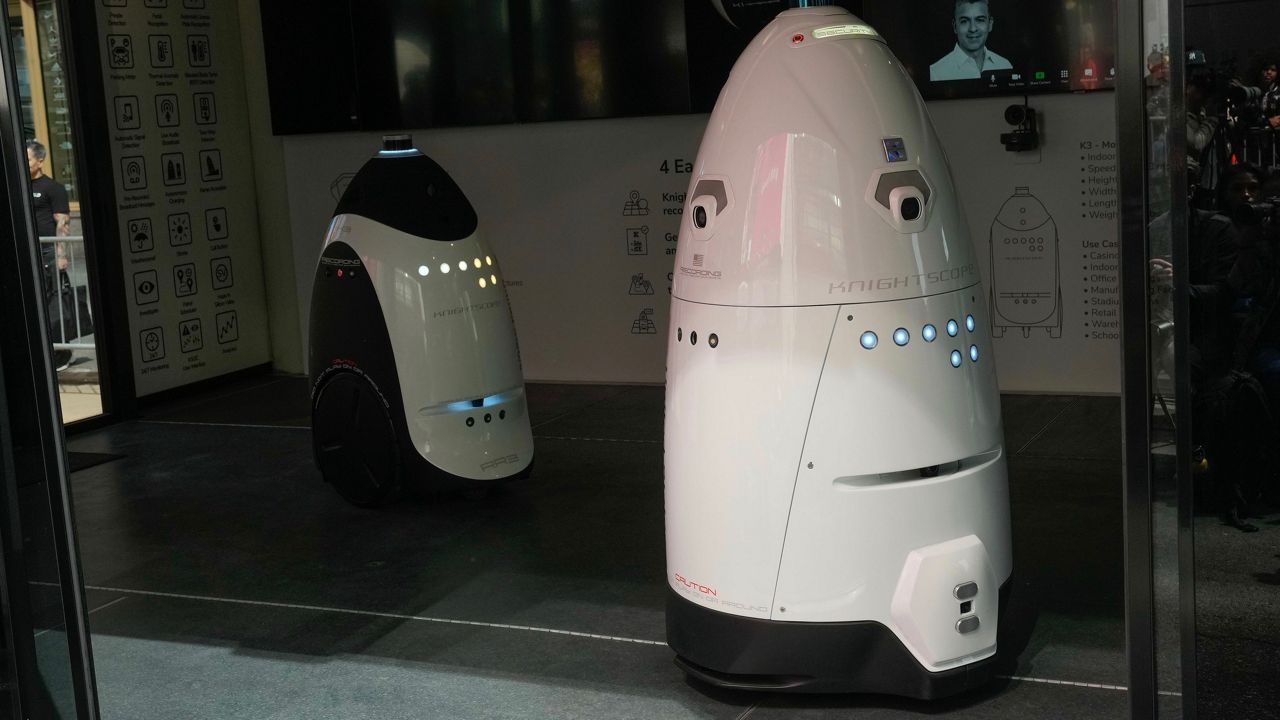

The robot, which resembles a knock-off Star Wars droid, will patrol Times Square and some subway stations during a six-month pilot period starting in July. (It will partner with a human officer.) Though K5 has mostly made headlines for knocking over a toddler and “drowning itself” in a shopping mall fountain, police officials said the robot will use artificial intelligence to alert first responders about potential crime incidents.

Adams and police officials pitched Spot as life-saving tactical equipment that can be used in situations — such as hostage negotiations — when sending a person is unsafe. K5, however, is a 400-pound moving cone of surveillance technology that its maker says is designed to recognize people, capture license plates and record audio. (The NYPD has said it will not use the K5 for facial recognition.)

Experts on surveillance and policing say they’re concerned that the new robots, and especially the K5, will further encroach on privacy in an already heavily surveilled city, and that the Adams administration and the NYPD have not sufficiently disclosed how they’ll use the robots’ advanced capabilities.

“That's not just disrespectful, it's dangerous,” said Donna Lieberman, the executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, in an interview. “And it risks us getting into the use of surveillance, and data collection and intervention, in ways that New Yorkers had no idea they were signing up for or being signed up for.”

Adams’ interest in technology — he took his first paychecks in cryptocurrency and plans to launch a one-stop-shop app for city services — has extended to policing from the start of his mayoralty. Last April, he said that he had directed his deputy mayor for public safety, Philip Banks III, to travel to conferences to look for new policing technology.

Adams has suggested that criticism of the robots comes out of a general fear of technology. Speaking at a recent event showing off the Spot robot and surveillance drones, he claimed that the city’s government had so far failed to embrace technology because it was “concerned about the small number of people who are afraid of change.”

The city is already laced with surveillance cameras, including more than 10,000 in the city’s subway system — where the K5 may spend part of its time patrolling. The robot, however, adds a new level of intrusiveness to the routine surveillance New Yorkers may feel used to now, said Peter Asaro, a professor of technology studies at The New School.

“A lot of what the camera sees is already kind of in public view,” Asaro said in an interview. “But these are really new technologies that bring into public view things that we assume are private. So I think that's a real game changer.”

Elected officials, public safety researchers and legal experts say that the city is not being fully transparent about the technological prowess it is purchasing under city law — specifically the Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology Act of 2020.

Angel Diaz, a visiting assistant professor at the University of Southern California’s Gould School of Law, noted that the NYPD’s legally required disclosures of the robots’ surveillance capabilities does not include services that the K5’s manufacturer, Knightscope, advertises for the robot. Diaz called the department’s disclosures “woefully inadequate.”

The NYPD’s disclosures mention thermographic imaging, which can examine temperature differences in the environment, and “situational awareness” cameras used for remote-controlled video capture. The disclosures do not mention license plate reading and do not discuss the possibility that the video recorded by the robots can be run through facial recognition software. (Knightscope says K5s can also recognize faces with internal proprietary software.)

The disclosures also say that, unlike the NYPD’s other imaging technologies, the robots can record thermographic and situational footage — and that the department can retain that footage for up to 30 days, and share it with prosecutors and government agencies that may request it in connection with criminal investigations. The data, the disclosures say, can be used for law enforcement purposes as well as “other official business of the NYPD.”

The NYPD has also not laid out the role that artificial intelligence and proprietary algorithms — which are frequently shown to have racial biases — play in the robot’s software, Lieberman said.

“The mayor and his team have resorted to a really, really disrespectful end run around the reporting requirements,” Lieberman said.

“Everybody would probably agree that if you can use a robot responsibly in a situation where there is a risk to human life, I mean, duh, of course,” she added. “But that is so far afield from the massive surveillance machine that we are coming up against.”

In an emailed statement, an NYPD spokesperson said that the K5 robot does not have facial recognition capabilities, and that during the pilot period, the thermal imaging cameras will only be used “for fire detection purposes.”

“The NYPD takes its responsibilities under the POST Act seriously and is transparent in its Impact and Use Policies,” the spokesperson said.

In a City Council hearing Wednesday that focused on the use of biometric surveillance technology in the city, council members pressed city officials on whether agencies collect such data and how it is stored or shared, and how the administration is ensuring compliance with privacy laws.

“There’s a big and valid concern in our communities about who is doing the oversight for PD,” said Councilwoman Jennifer Gutiérrez, chair of the technology committee, referring to the police department’s use of biometric surveillance. “Oftentimes, we are vulnerable. Oftentimes, New Yorkers have no sense if their information is getting collected.”

Ryan Birchmeier, the deputy commissioner for the Office of Public Information, said that the department was in compliance with disclosure laws.

“I just don’t believe that,” Gutiérrez said.