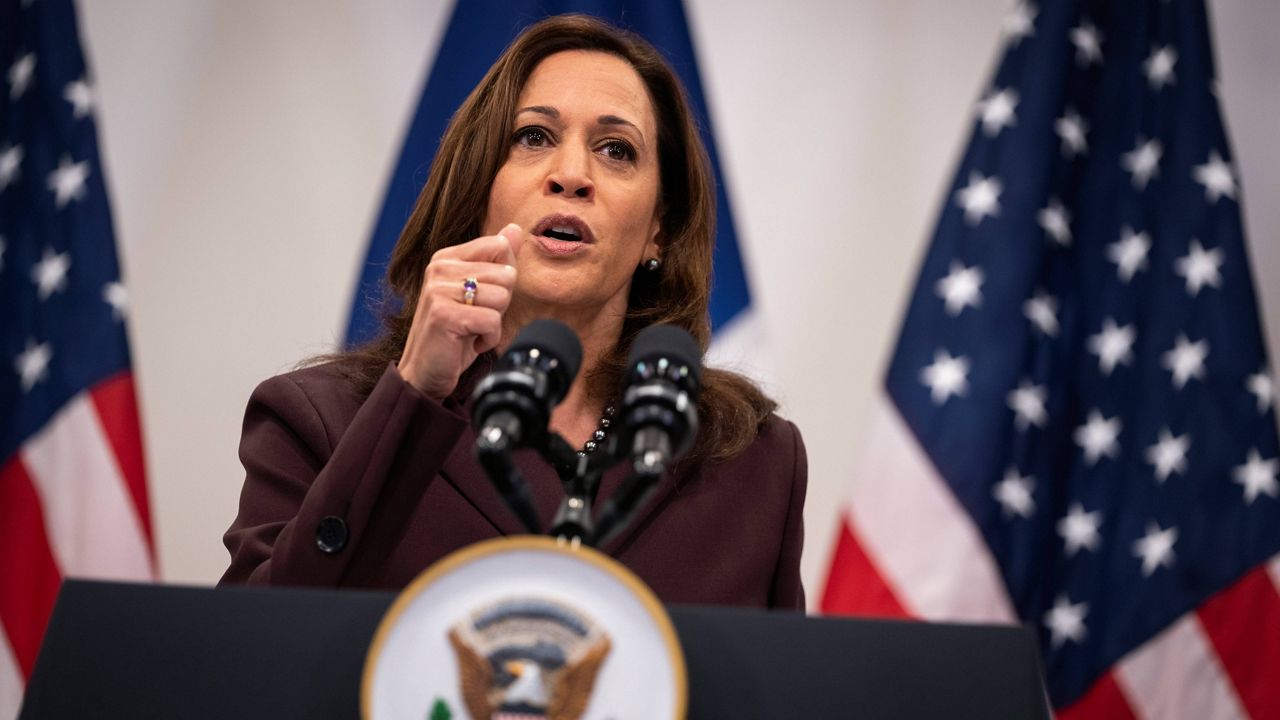

Vice President Kamala Harris opened the White House’s first summit on maternal health on Tuesday, calling on both the public and private sector to address pregnant women’s health, safe childbirth and postpartum care, as the United States maintains the highest maternal mortality rate among similar, developed nations.

The day-long gathering included members of congress, health care providers, advocates like Olympian Allyson Felix and top health officials, as the administration rolled out new initiatives to improve birthing outcomes and health coverage for women and their newborns after birth.

“This is a hard truth. Women in our nation are dying — before, during and after childbirth,” Vice President Harris said to begin the summit on Tuesday. “When we know that, we should do something about it.”

Harris pointed out that Black women are three times more likely than white women to die from pregnancy-related complications, while the risk is more than twice as likely for Native American women and 60% more likely for women in rural areas.

“We know a primary reason why this is true: Systemic inequities — those differences in how people are treated based on who they are,” she said. “When it comes to pregnancy and childbirth, these systemic inequities can be a matter of life and death.”

The U.S. rate of pregnancy-related death is more than 17 per 100,000 births, according to the Commonwealth Fund, compared to half that in countries like Canada and France and rates as low as three or less in comparable nations like the Netherlands, New Zealand and Norway.

Harris announced two new initiatives from the Biden administration on Tuesday: urging states to expand Medicaid coverage to cover women for a full year after they give birth and a plan to create a new “Birthing-Friendly” hospital designation, the first label of its kind to focus on maternal care.

“We are expanding our provider quality measurement programs, and we're working to reward high quality care,” said Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure.

Expanding Medicaid and children’s insurance for women and newborns to one year after birth would cover an additional 720,000 Americans annually for care like pelvic exams, vaccinations and more, according to a new report from the Department of Health and Human Services evaluation division. The expansion is also a proposal included in the Democrats' social spending bill, which is still in Congress.

Typically, mothers are covered for a minimum of 60 days after birth. States like Virginia, Illinois and New Jersey already agreed to expand coverage, Brooks-LaSure said.

Harris on Tuesday also sat down for a conversation with Allyson Felix, five-time U.S. track and field Olympian and advocate for maternal health.

Doctors diagnosed Felix with severe preeclampsia in 2018 when they realized her blood pressure was high and her daughter’s fetal heartbeat was low. Her daughter Camryn, now three, was born via emergency C-section at 32 weeks.

“We all walked out [of the hospital] together,” she told Harris. “As we know, there are so many women who that's not the story. And so my eyes were opened.”

“I remember my time in the hospital and just feeling like I didn’t, I wasn't prepared for this,” she said later. “I had great health care. I’m very fortunate and very blessed. But I still found myself in the situation [and] hearing from other women that their pain wasn't believed.”

Felix noted that the risk of pregnancy “doesn’t discriminate” and it’s especially dire for women who don’t have access to good care postpartum, when mothers may not have easy access to return to a hospital, such as in rural areas.

“A lot of times we run into problems because women are bringing up that something feels wrong afterwards, and it's being dismissed,” she said. “In rural areas, having that access and those resources is huge.”

Harris and health experts on Tuesday stressed that most maternal health issues and deaths were preventable with the appropriate access.

The United States’ maternal mortality rate also increased by more than 26% from 2000 to 2014 in most states, according to studies.

“This is a fight that we can win. We already have the tools to save women's lives,” said Anushay Hossain, author of The Pain Gap, at Tuesday's summit. “No woman should be dying giving birth in the richest democracy in the world.”

When in the Senate, Vice President Harris helped craft the Momnibus, a 12-bill package intended to address women’s health, both clinically and through outside factors like housing security, climate change and more.

Portions of the Momnibus are included in President Joe Biden’s social and climate spending bill, the Build Back Better Act, which passed the House last month and is being negotiated in the Senate.

The BBB Act currently includes more than $1 billion in funding for maternal health, including money to expand the workforce with people like doulas and midwives, plus expand research on maternal health at minority-serving institutions.

At the White House on Tuesday was Democratic Rep. Alma Adams of North Carolina, who reintroduced the Momnibus package in February along with Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., and her Black Maternal Health Caucus Co-Chair Rep. Lauren Underwood, D.-Ill.

“My work in Black maternal health began when my daughter, a Black mom herself, survived a complicated pregnancy that almost claimed life after her complaints of pain in her abdomen were overlooked by her physician,” Adams said, later adding: “It's really about equality.”

A variety of companies and organizations on Tuesday also made new commitments to addressing maternal health, like CVS, Lyft, Uber, Pampers and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association.