John Duffy was on his usual weekday commute down the West Side Highway that Tuesday 20 years ago when he saw a plane following the route of the Hudson River.

He remembers wondering why the plane seemed to be flying so low, but he quickly brushed it off and refocused his attention on the traffic.

It wasn’t long after that Duffy heard the first news report that a plane had struck the World Trade Center.

His office at the investment banking firm Keefe, Bruyette & Woods was on the 88th and 89th floors of the South Tower, right above the point of impact of the second plane that hit the towers that infamously clear-skied morning.

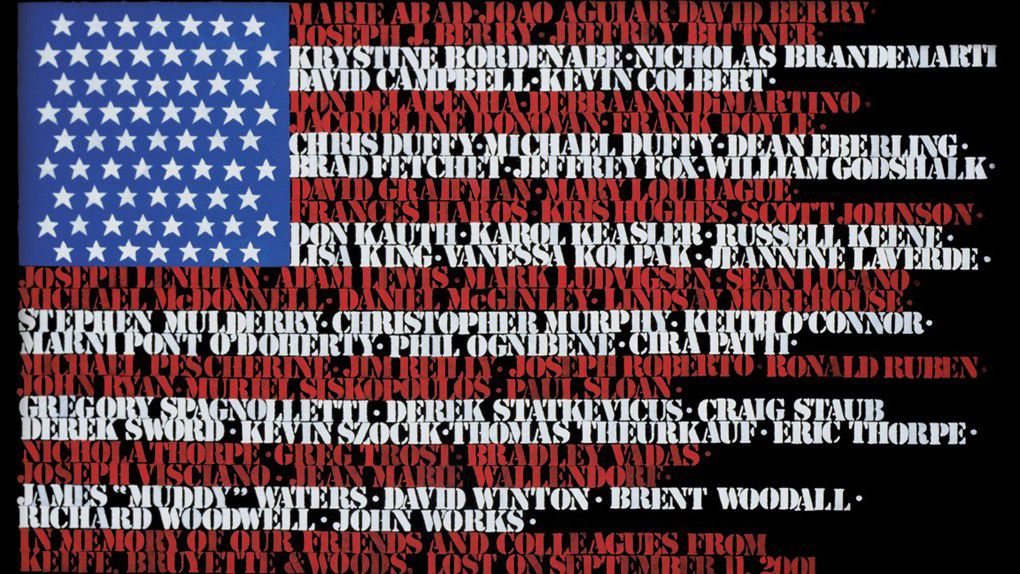

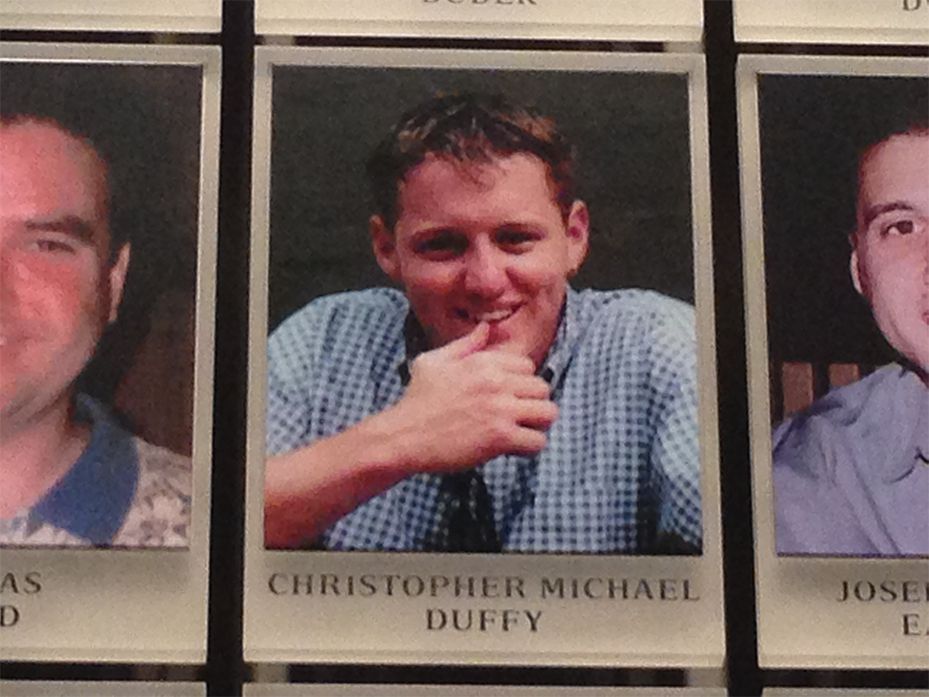

The firm lost 67 people that day, including most of the research and trading departments. Duffy’s 23-year-old son, Christopher, an assistant stock trader at the firm, was among those who perished.

He’s certain now that that plane he had seen was that first plane that hit the North Tower.

But driving along the Hudson that morning, he had difficulty grasping what he was looking at.

“I was still not believing it -- that a plane would fly down and certainly they didn’t think it was an attack on our nation,” he said, referring to the news reports on the radio that morning.

It wasn’t until he heard the second report that another plane hit the second tower that he realized something was seriously wrong.

He pulled off the highway and parked near Madison Square Garden.

After a failed attempt to take the subway downtown — the trains had stopped running — he began walking toward his office.

He had only gone about four blocks, he recalls, when he saw the first tower fall.

“Everybody that was facing south just stopped in their tracks and everybody that was walking in the other direction saw people pointing downtown,” Duffy said. “The whole intersection came to a standstill.”

Duffy had to deal with the tragedy not only as a leader of a company that lost about one-third of its staff, including his co-CEO and friend Joe Berry, but coping with the loss as a father as well.

“When you go through something like I did, you either get through it or you don't,” said Duffy, 72, who now splits his time between Florida and New Jersey.

KBW was a close-knit firm with 171 employees in its New York office.

“They're my family,” said Jackie Day, who has worked at KBW for 30 years. “I've grown up with all of them. And that was what was so hard of all the 67 we lost, I knew every single person on our list.”

“For all things considered, it was kind of a small company that really felt like a family,” said Caitlin Duffy, John’s daughter, who did not work at the firm. “We would go there every Christmas Eve as kids and knew everyone that they worked with.”

In 2001, the firm’s stock was entirely employee-owned, which meant the company had to pay out about $40 million to the families of those who died, Duffy said.

They had enough capital on hand, but after losing so much of their team, all of their company documents and headquarters, the firm’s survival was very much in question.

Duffy didn’t return to work until after Christopher’s memorial, which was held on Sept. 25, but when he eventually did, he said he was “all in.”

“It was actually cathartic,” he said. “When I woke up in the morning, instead of feeling kind of sorry for myself, having lost a son, or for the firm’s family members that lost a son or a sibling, it gave me some purpose.”

He tried to attend as many memorial services as he could, but there were so many that some memorials were scheduled on the same day, including the services of his son and co-CEO.

“The extent of which he had to mentally compartmentalize and deal with — it was something that I think has worn on him more than I'll ever really truly understand,” Caitlin Duffy said.

Rebuilding the firm was more than an outlet for healing though. The financial responsibility to the victims’ families weighed heavily on those who remained.

“The people who survived wanted to rebuild the firm because we felt that was the best way of what we could do for the folks who hadn't survived — for their families, in terms of providing financial assistance,” John Duffy said.

On the first and second anniversaries of the attack, the firm donated commissions from those days, about $15 million, to a “KBW Family Fund,” said Duffy. They also continued to pay the health insurance premiums for the families for five years.

“In the early days, it was tragic and you just did whatever you could to help because they needed help on so many levels,” said Neil Shapiro, who has worked with KBW in communications since 2000. “But then, as they committed to rebuild and seeing how they took care of the families, seeing what they did for surviving employees, and just seeing how they went about rebuilding their business day-by-day, it was extremely inspiring.”

The firm opened new offices in midtown in 2001 and eventually opened offices in London, Hong Kong and Tokyo. And in 2006, the firm went public; the stock jumped 30% on the first day of trading on the New York Stock Exchange, Shapiro said.

KBW now employs just under 350 people. It merged with Stifel Financial, a St. Louis-based brokerage and investment banking firm, in 2013, but many, like Day and Shapiro, still consider 9/11 part of the firm’s DNA.

“It's always part of our thought process when September starts to come up,” Day said.

Each year they hold a moment of silence at 9:03 a.m. — the time the second plane hit the South Tower. The firm will be taking that moment of silence on the New York trading floor on Friday this year as the upcoming 20th anniversary falls on a Saturday.

They also hold a private event at the Central Park Zoo, where a plaque honoring the lives the firm lost is located. The event is open to alumni of the company, family and friends, vendors that the company works with and more.

“I'm very proud of what we've done since that time — that KBW still exists, that we still have a core group of pre-9/11 folks as this date approaches, we lean on each other,” Day said. “We reach out to each other. There is just a sense of community that comes back to us that is irreplaceable.”

Duffy stepped down as chairman and chief executive in 2011 and retired in 2018.

But his time at KBW and the impact of 9/11 stays with him.

He said he’s more decisive now because he understands that time isn’t something that can be taken for granted.

However, he makes sure to give himself grace and encourages others to embrace it as well.

“You're not going to be right 100% of the time so if you make a decision and you're wrong — don't beat yourself up about it,” he said. “Tomorrow's another day.”