NEW YORK — When DonChristian Jones founded Public Assistants in the summer of 2020, he had no idea it would quickly become a cultural hub.

At the time, the city was going through a huge uprising after back-to-back incidents of police brutality around the country and the COVID-19 pandemic upending the economy.

“People were hitting the streets for George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and all of my peers, students, and family were out of work, lacking health care, really enraged, and needed outlets to express their feelings,” said Jones. “I just realized we needed a place to commune safely and create, if only just, like, feed each other, rest and not be in protest at all times.”

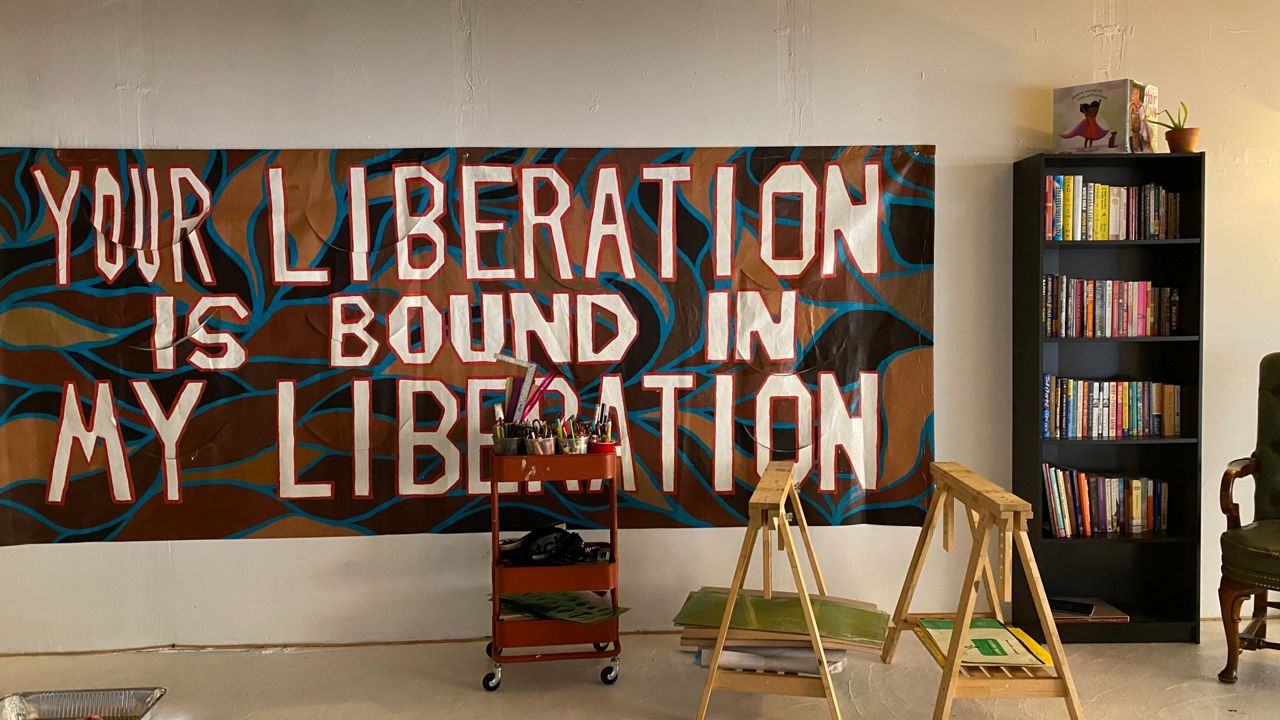

As an artist and teacher, Jones' original idea was to create a space for people to make art.

Flash forward nine months and the renovated laundromat in Crown Heights is now a place where young people can gather to refurbish bikes, garden, and do fitness training.

“I just wanted to paint murals and make banners, but sure enough now we're screen printing and sewing clothes and fixing bikes and doing acupuncture,” he said. “That was beyond my wildest dreams, but I'm so excited by all that and to think that those things too can maybe fall in the ethos of art making and performance.”

Jones said he felt fortunate in that he was able to generate a lot of interest in Public Assistants and solicit donations to get the space off the ground.

But that’s not always the case, especially amidst a pandemic when so many people are out of work and city budgets are strained.

“In order to sustain, you often have to be constantly applying for grant opportunities and fellowships and these opportunities for funding simply to sustain one's own career,” he said. “But not everyone has that access to sources of funding.”

The cultural and performing arts sector has been one of the hardest hit industries by the coronavirus pandemic. And artists and performing arts companies feel the recovery efforts have left them on the periphery.

Mayor Bill de Blasio and Governor Andrew Cuomo both recently announced efforts to revive the arts through their respective Open Culture and NY PopsUp plans.

The city’s Open Culture program, similar to Open Streets and Open Restaurants, will allow cultural organizations to apply for single-day permits to provide outdoor entertainment at 115 street locations across the five boroughs.

The governor’s plan includes 300 events over 100 days around the state and will eventually ramp up to include spectators as the state moves toward venues reopening with COVID-19 testing protocol in place.

It’s a start, but BIPOC artists say it’s a temporary solution and worry that access to this support may not be equitable.

“There’s the same obstacles that are faced with getting support from any government agency,” said Alejandra Duque Cifuentes, executive director of Dance NYC. “When there are fees associated, there are financial precautions to participation that arise. Not everyone has $20 to submit a permit multiple times.”

She points out that navigating these types of programs requires a baseline of understanding of how city bureaucracy works, which could be difficult for people who have felt historically disenfranchised from the system.

And even though applying for a license in a program like Open Culture means interacting with the Department of Cultural Affairs, there could still be hesitation that arises from interaction with any city agency.

“Dealing with city government is often related to dealing with law enforcement, which as we know, comes with harm to Black and BIPOC folk and so I think that's part of what's tricky here,” said Duque Cifuentes.

And while people like Duque Cifuentes are happy to see the needs of artists being addressed by elected officials, she wishes that the arts could have been prioritized in the way the restaurant and service industry was last year.

“We really would have preferred the same expediency that was had around the restaurant industry being able to open last summer for arts and culture,” she said. “It's an important first step. Do I think that it is sufficient to address the needs of BIPOC artists or to address the needs of the arts and cultural community? Absolutely not.”

At a Cultural Affairs City Council hearing last month, one of the major themes brought up in various testimonies was the importance of access to space for artists and performers.

It’s why Councilman Jimmy Van Bramer sponsored a bill that would enact a study on the real estate issues that cause cultural displacement.

“We never prioritize the arts in the way that we should,” said Van Bramer, who chairs the Cultural Affairs Committee. “When bad times come, which are currently here—that's when we traditionally say all of these things are expendable. All of these things are luxuries in the good times, but simply unaffordable and not a good use of resources in bad times. ”

Jerome Harris of the Music Workers Alliance testified at the hearing that he supported the study, but that the “loss of cultural space in the city has been a problem for decades” and has only gotten worse since the pandemic.

This displacement is something Dance NYC has been studying for a while.

“Our data has shown that the number one issue that right now is impacting individual arts workers, as well as organizations, businesses and institutions is rent,” said Duques Cifuentes, who also provided testimony at that hearing. “And very rarely, in our research, have we found that there is one answer to the needs of everyone. This is one of those rare moments.”

For black artists in particular, access to space means so much more than physical location. It means a chance to build community and gain a sense of agency.

Jones has had access to studio space as an individual artist in the past, but building a space like Public Assistants was a first for him.

“To have space that is collective, that can be cultivated in the ways we have—you're providing that neighborhood or that community with so much agency to learn and to grow on their own,” he explained.

He describes the past nine months at Public Assistants as one massive skill share.

“Now we know how to make banners and stitch them and screen print shirts and build brick fires out in the lot and grow herbs,” he said. “It's just, it's incredible.”

But Public Assistants is currently facing eviction.

It’s a common story in this city.

Part of Councilman Van Bramer’s efforts include the creation of a city-run agency that can help oversee cultural spaces like they have in cities like Seattle where they’ve developed systems of community ownership for arts spaces.

“I think that's really critical here, particularly for black and brown cultural communities,” said Councilman Van Bramer. “Most of our small community-based cultural organizations, if they have any space at all, rent that space and that makes them incredibly vulnerable to changes and the real estate market in their neighborhood makes them vulnerable to speculation.”

For Duque Cifuentes, this precarity has a pretty direct line through history.

“We know that historically in the U.S. that lineage of access or lack thereof to land ownership is directly a child of the slave trade,” she said. “It's directly along race lines so when we look at the performing arts sector, and we look at supporting Black, Indigenous, people of colors, disabled, immigrant artists—we're also looking at a generation of people that do not have easy access to land ownership, to rentals to leases.”

She said that there are many BIPOC organizations that are often priced out of their leases or mortgages and often negotiated into commercial rent contracts that are extractive for communities.

And though Jones is in the midst of an eviction crisis, he doesn’t want this current conflict to define what they’ve been able to build at Public Assistants.

“I don't want to exacerbate that,” he said. “I want to maintain a safe and brave space for everyone that already comes here. A project like this has even opened my mind further to collaborative art making and while it's not my own personal studio, per se, there's all this wall space inside and out and floor space to work on and call people to help. It’s just a whole different landscape of making.”