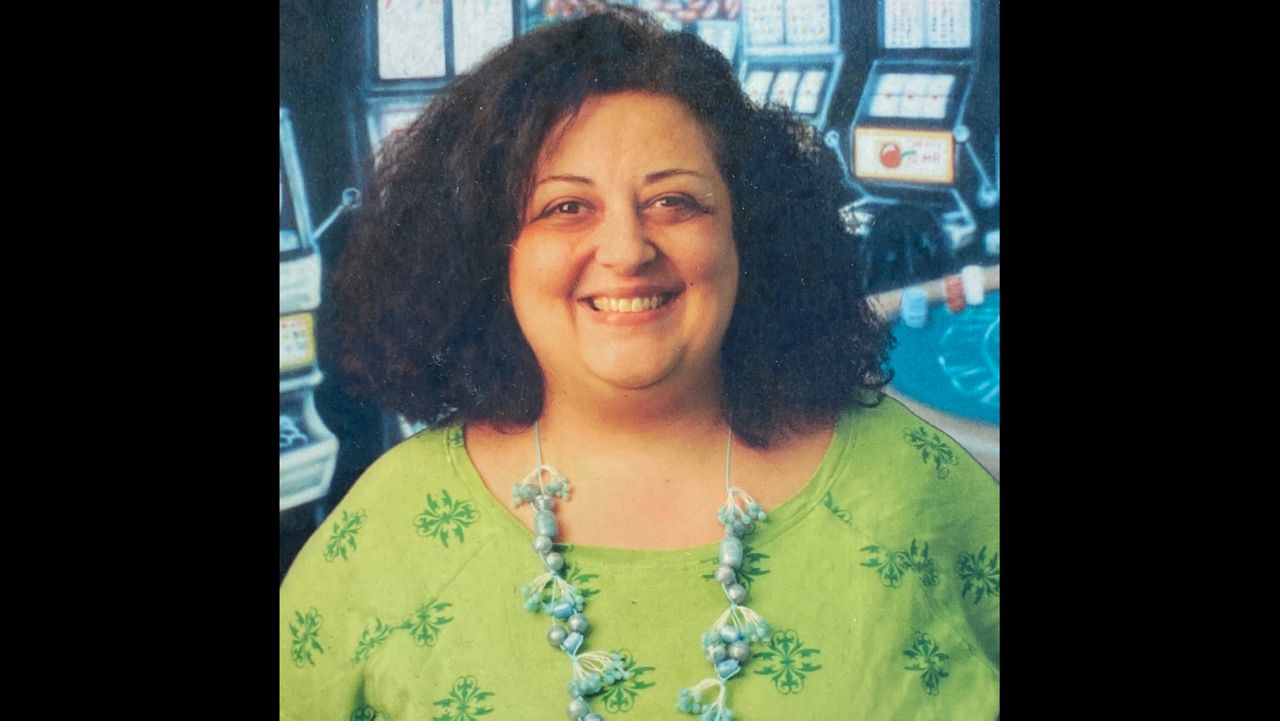

Anna Lyrist loved people.

“She was very social,” her stepdaughter, Catherine Palomino Valadez said. “She was insanely social. She loved to talk. She would talk your head off. It would drive you nuts.”

Her zest for life and her optimistic view that there is always hope was put to the test when Lyrist was diagnosed with coronavirus.

“She said no matter what, keep me alive, I will fight,” Valadez said. “I kind of feel the opposite, but she believed in miracles.”

Her health was far from perfect. She struggled with obesity and badly needed a hip transplant but wouldn’t get the surgery because of her fear of COVID-19.

It was three days after Orthodox Easter Sunday, April 29, when Lyrist was admitted to Mt. Sinai Hospital in Astoria, Queens, suffering from shortness of breath, fever and chills. Always outspoken, she texted to say she wanted to go to a different hospital.

“She started texting when she was admitted,” her stepdaughter said. “She knew she was high risk. She said she’d rather be in Flushing Hospital, but the EMTs didn’t want to take her there. She said she had family that worked there and she wouldn’t be alone. She said, 'please pick me up and take me to Flushing.'”

Doctors agreed to move her, but, at first, there were no available beds. Then, her blood oxygen dropped to dangerously low levels.

“Every day when we would FaceTime I noticed her masks getting more invasive,” her stepdaughter said. “They put her on an IPAP mask, then she needed to be ventilated. She was worried about her cellphone battery running out. She was so superstitious, when she was signing the health care proxy form I heard her saying, ‘this is a black pen. Do you have a blue one?' I thought, that’s so her, she’s in the hospital, things are getting serious, and she’s worrying about the color of a pen.”

Lyrist’s condition continued to deteriorate, but her stepfamily refused to give up. Doctors told Valadez she probably wouldn’t make it, that there was no hope to be had.

“We told her Anna believed in hope,” Valadez said. “I put my beliefs aside and asked him to do the same. I knew what she wanted, so I told them, whatever you have to do to keep her alive, do it.”

Valadez decided she would do all she could to make sure Lyrist was getting the best possible care. She spent her days and nights researching possible treatments and medical terms, carefully tracking her stepmom’s progress, and setbacks.

“If they would tell me her creatinine was low, I’d write it down and Google it,” she said. “I started a spreadsheet with checks for kidney function, to see if her ventilator settings were consistently high and if she was on or off her blood pressure medicine. I would read about it all so when I talked to the doctors I wouldn’t be wasting their time, I’d be able to ask, ‘have you tried this?’”

When she heard the drug Remdesivir was showing hopeful signs, Valadez asked the doctors to try it, but they said the hospital didn’t yet have a supply.

“The next day they called and said, 'we have it, let’s go over the risks and benefits,'” she said. “I knew she wanted every possible chance.”

But it was too late. Twenty-four hours later, on May 6, Anna Lyrist died. Doctors said it was a heart attack. It was one week after she was put on a ventilator.

“One day I couldn’t reach her, and I said we’ll call back,” Valadez said. “At 1:00 a.m. a nurse called and said she was in Anna’s room, next to her, and I’m putting you on speaker. I said, 'Anna, Anna, I love you, it’s me, keep fighting.' I knew she could hear me and that meant a lot to me because, to this day, what comforts me with Anna is that she knew I loved her and I knew she loved me, and I was able to be totally involved with her care. I was so happy I could do that for her.”

Anna Lyrist lived life on her own terms. She was born in 1953 and raised in Washington Heights, the daughter of immigrants from Karpathos in Greece.

“She was always very proud of her father,” Valadez said. “She said he was one of Aristotle Onassis’s accountants.”

She attended St. Spyridon, a Greek Orthodox grammar school and then went on to Columbia University’s Teachers College. Proud of her Mediterranean looks, she boasted that she once marched in the Greek Independence Day Parade.

Brave and independent herself, Lyrist went off to Spain for a year to study. It was there that she discovered a whole different culture, and it was love at first sight.

“She loved the Spanish culture: the food, the passion, and the Spanish people," Valadez said. "I helped her update her resume once, and I asked if we should, maybe, delete the part about studying in Spain decades before, but she said, ‘no, it’s important to me.'”

She became a professor at Hofstra University, then Pace University, teaching English as a Second Language. She met her future husband, William, a Peruvian immigrant, in the Teacher’s College cafeteria. He taught math.

“My dad said, ‘wow! She’s beautiful,'” Valadez said. “They struck up a friendship, married and divorced all in a very short time.”

But Lyrist had already become an inseparable part of the family, a mom to Catherine.

“I was four or five when they married,” her stepdaughter said. “Anna was there. In the beginning it was dad, Anna and me. She’s the first person in my life I loved that I lost.”

After the divorce, Lyrist moved a block away, wanting nothing more than to be near her family. William would marry again and have four more children. When they decided to move to Long Island, Lyrist said she wanted to move there, too, just to stay close.

When Lyrist died, her family worried, having heard on the news about bodies of COVID victims being found in freezer trucks in the city. But fate had a role to play in how the family would say their final farewell.

“She wanted to be buried with her sister in St. Michael’s Cemetery,” Valadez said. “So we thought we’d have a ceremony in a parking lot. But the day before the funeral, we got a call from someone in the Greek Orthodox Church, who said he had read about Anna in a local Greek newspaper. He said he wanted to offer us St. Demetrios Church in Astoria, and that His Eminence, Archbishop Elpidophoros would like to attend. I think she would have been pleased.”

Despite their somewhat “untraditional” family, Valadez said her grief at losing Anna Lyrist couldn’t be more painful.

“I feel like me and Anna have a special connection,” she said. “She was there for me when I didn’t have any brothers and sisters and she would let me sit on her lap. We have something very special. She would call a million times a day, just to ask about the kids. She’s my mother. She called me 'Mickey Mouse'. She was the closest person to me. I was so lucky I was able to be there for her in the end.”