Henry Arthur Jackson spent a lifetime defying the odds.

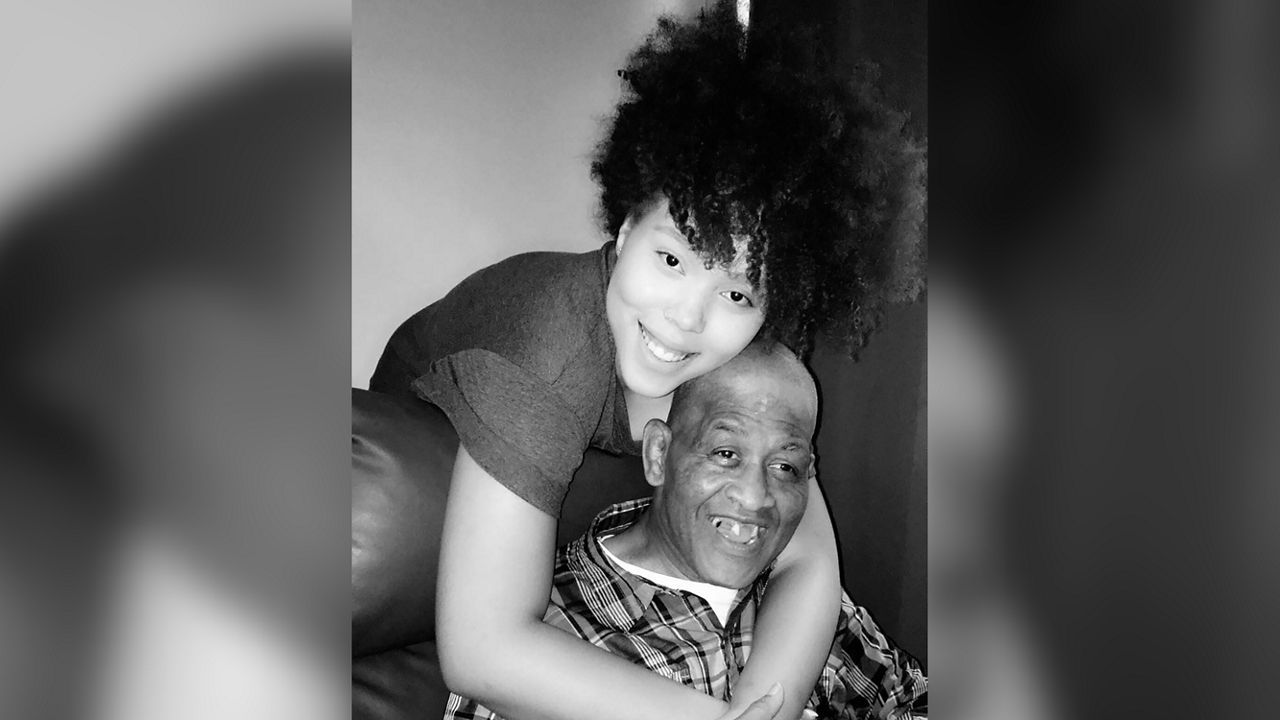

His sister said they had an unbreakable bond.

“Henry was born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1949, at a time that was not favorable to persons of color,” Tracey Jackson said. “He was a healthy, beautiful, 10-pound baby boy; his mother and father’s first child.”

None of them could know that one day, he would have an heroic place in a most tragic and shameful part of New York City’s history.

When he was four months old, Henry was diagnosed with spinal meningitis. His mother, Edna, was just 20 years old. After a seemingly endless round of hospitalizations and doctor visits, she received the terrible news: her son would never walk or talk. He would probably not live beyond his fourth birthday. It was a prognosis Edna Jackson refused to accept.

“Unfortunately, her husband did not agree with her spirit and determination that her son would live,” Tracey Jackson said. “She had to raise us alone because our dad ran away. He couldn’t deal with his son being in this condition.”

When Henry, who his family called “Dusty”, was just two years old, he offered his mom a glimmer of hope.

“On one stormy, summer day, while visiting his grandparents, Henry reaches up his hands,” his sister said. “He smiles and stands up, arms stretched up as if someone was holding his hands, and he began to walk.”

Tracey Jackson said that was the moment that changed everything.

“His mother made the decision at that point that her child would live and not die,” she said. “She packed her baby up and moved to New York City and brought him to where he would have a chance at life.”

But that life was not easy for the single mom of two young children, one of whom was profoundly disabled. Edna Jackson needed help.

“Our mother couldn’t work and take care of him,” Tracey Jackson said. “When he was seven or eight she made the heartbreaking decision to put him in a facility.”

That facility was the now-infamous Willowbrook State School on Staten Island, described by then-Senator Robert F. Kennedy as “a snake pit” for its overcrowded, filthy conditions and the abuse of patients, many of whom had been abandoned by family members or the system.

They also became subjects of a hepatitis “study”, described by one medical expert as “the most unethical medical experiments ever performed on children in the United States”.

Tracey Jackson said her mom would pick Henry up on Friday and bring him back every Sunday. Because he was unable to communicate, she had no idea of the horrors going on inside.

In 1983, the state announced plans to close Willowbrook. Henry Jackson was one of the last to leave in 1987, when he was 38 years old. He was part of a class action lawsuit that would forever change the way the state treated people institutionalized with mental health issues. He was the last surviving member of that lawsuit.

Henry’s life would change forever when he was placed in a group home in Upper Manhattan, run by Birch Family Services.

“They became our new family,” Tracey Jackson said. “I say family because at that point, the care that was given to him made him feel love and genuine care. He lived a wonderful, incredible life, full of adventure and music.”

The man they came to call “Papa” was the longest resident of his group home on West 162nd Street.

“He was a grumpy old man,” his sister said. “He loved to draw. A long time ago he did a drawing of Yankee Stadium and it was shown at the state capital building in Albany and at Rockefeller Center. He loved music and he loved to sing, loved to do all the things they said he couldn’t do.”

Henry’s mother, who remarried, becoming Edna Jackson-Jacobs, developed Alzheimer’s in 2005. She would pass away in 2014. Tracey Jackson became her brother’s primary caregiver. Even though she was living in Alabama, she was happy knowing her brother finally seemed to be enjoying his life.

“He always had someone with him,” she said. “He had a one-on-one caregiver, 24/7. Two gentlemen, Tyrone and Lawrence, loved to take him out into the area to the Apollo, to all the music venues and museums. He did the things he may not have done since he was a little boy and did it with my mom. He went to The Bronx Zoo. Before he stopped walking he would go with someone to the barber shop and the grocery store. Everybody knew Mr. Jackson. Everybody loved Mr. Jackson.”

When the group home temporarily closed, Henry Jackson was moved to a local nursing home, the Isabella Geriatric Center on the Upper West Side, where nearly 100 patients are believed to have died from coronavirus.

He was admitted to Columbia Presbyterian on March 23 after suffering a seizure.

“They were gonna test him for the virus,” Tracey Jackson said. "Then they came back the next morning saying he has it. That was the beginning of the end.”

The hospital called every day to ask her permission to put her brother on a ventilator, but it never happened.

“The most confusing part for me is I was called every day from the 30th until he died asking for my consent,” she said. “Why was I giving consent for something that they weren’t going to do?”

On April 6, the hospital said they were doing an EKG before, finally, ventilating him.

“They said they did an EKG and he had had a heart attack from struggling to breathe for so many days,” she said. “They asked for consent to put him in the hospice wing. As soon as they rolled him in, he died.”

As it was for so many who lost a loved one to COVID-19, the hardest thing for Tracey Jackson was not being with her beloved brother when he passed away.

“It was so hard not being able to come to New York City,” she said. "They knew I’d have been on the first train to get there just to touch him and say he’d be OK. One of the staff at the hospital snuck in his room with their iPhone and FaceTimed me so I could see him and talk to him.”

Despite everything Henry Jackson went through in his life, what his sister will remember most is his strength.

“My brother had survived so many things,” she said. “Epilepsy, grand mal seizures over and over again, 70 years of seizures. He survived all of that, and at his last doctor’s appointment he came back with a clean bill of health. It’s just that he survived all that he survived and then he died of this.”

“I want him to be remembered for giving so much unconditional love to his family and to those who cared for him,” she said. “I want them to remember him as a survivor, not as someone who died of the virus but as a survivor who overcame so many obstacles, so many challenges and he always fought back and he always came back. He saw his 70th birthday, which is 66 more than they said he would have.”

Now his grieving sister is left wondering how to navigate life without the brother she loved so much.

“I will miss his laughter,” Tracey Jackson said. “I miss having conversations with him even if it wasn’t a real conversation. He’d say, I want my sister, and I could talk to him on FaceTime. I could see him. He’d tell me, ‘I love you, Tracey’. He was the love of my life.”